What is Software Testing and Why is it Important?

Software testing is the process of verifying that an application behaves as expected under different scenarios. It helps identify bugs, ensures that requirements are met, and improves overall software quality.

Without testing, defects can slip into production, leading to downtime, financial loss, and reduced user trust. Testing ensures reliability, maintainability, and customer satisfaction, which are critical for any successful software product.

A Brief History of Software Testing

The roots of software testing go back to the 1950s, when debugging was the main approach for identifying issues. In the 1970s and 1980s, formal testing methods and structured test cases emerged, as software systems grew more complex.

By the 1990s, unit tests, integration tests, and automated testing frameworks became more common, especially with the rise of Agile and Extreme Programming (XP). Today, testing is an integral part of the DevOps pipeline, ensuring continuous delivery of high-quality software.

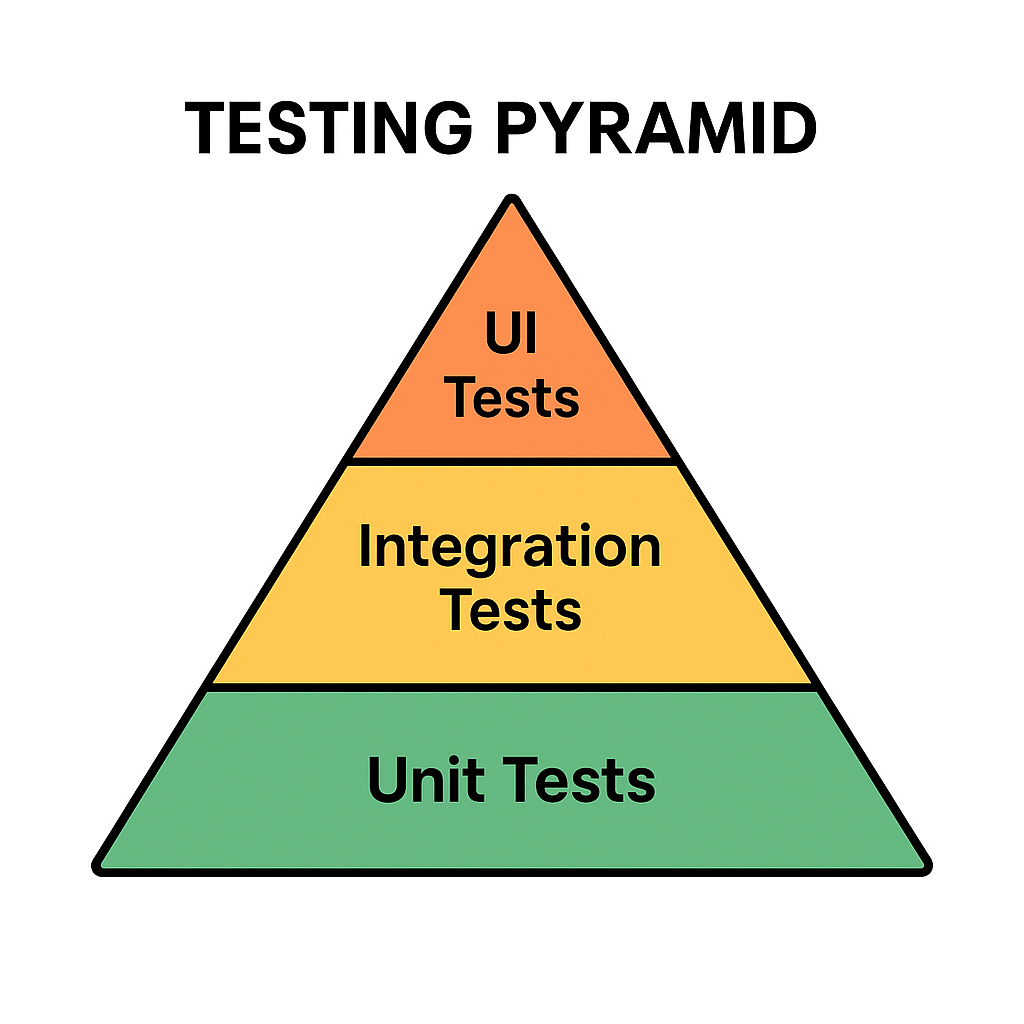

What is the Testing Pyramid?

The Testing Pyramid is a concept introduced by Mike Cohn in his book Succeeding with Agile (2009). It illustrates the ideal distribution of automated tests across different levels of the software.

The pyramid has three main layers:

- Unit Tests (Base): Small, fast tests that check individual components or functions.

- Integration Tests (Middle): Tests that ensure multiple components work together correctly.

- UI/End-to-End Tests (Top): High-level tests that simulate real user interactions with the system.

This structure emphasizes having many unit tests, fewer integration tests, and even fewer UI tests.

Why is the Testing Pyramid Important?

Modern applications are complex, and not all tests provide the same value. If teams rely too heavily on UI tests, testing becomes slow, brittle, and costly.

The pyramid encourages:

- Speed: Unit tests are fast, allowing developers to catch issues early.

- Reliability: A solid base of tests provides confidence that core logic works correctly.

- Cost Efficiency: Fixing bugs early at the unit level is cheaper than discovering them at production.

- Balance: Ensures that test coverage is spread across different levels without overloading any one type.

Benefits of the Testing Pyramid

Faster Feedback: Developers get immediate results from unit tests.

Reduced Costs: Bugs are caught before they cascade into bigger problems.

Better Test Coverage: A layered approach covers both individual components and overall workflows.

Maintainable Test Suite: Avoids having too many slow, brittle UI tests.

Supports Agile and DevOps: Fits seamlessly into CI/CD pipelines for continuous delivery.

Conclusion

The Testing Pyramid is more than just a model—it’s a guideline for building a scalable and maintainable test strategy. By understanding the history of software testing and adopting this layered approach, teams can ensure their applications are reliable, cost-effective, and user-friendly.

Whether you’re building a small project or a large enterprise system, applying the Testing Pyramid principles will strengthen your software delivery process.

Recent Comments