What are Code Katas?

Code katas are short, repeatable programming exercises designed to improve specific skills through deliberate practice. Borrowed from martial arts, the term “kata” refers to a structured routine you repeat to refine form, speed, and judgment. In software, that means repeatedly solving small problems with intention—focusing on technique (naming, refactoring, testing, decomposition) rather than “just getting it to work.”

A Brief History

- Origins of the term: Inspired by martial arts training, the “kata” metaphor entered software craftsmanship to emphasize practice and technique over ad-hoc hacking.

- Popularization: In the early 2000s, the idea spread through the software craftsmanship movement and communities around Agile, TDD, and clean code. Well-known exercises (e.g., Bowling Game, Roman Numerals, Gilded Rose) became common practice drills in meetups, coding dojos, and workshops.

- Today: Katas are used by individuals, teams, bootcamps, and user groups to build muscle memory in test-driven development (TDD), refactoring, design, and problem decomposition.

Why We Need Code Katas (Benefits)

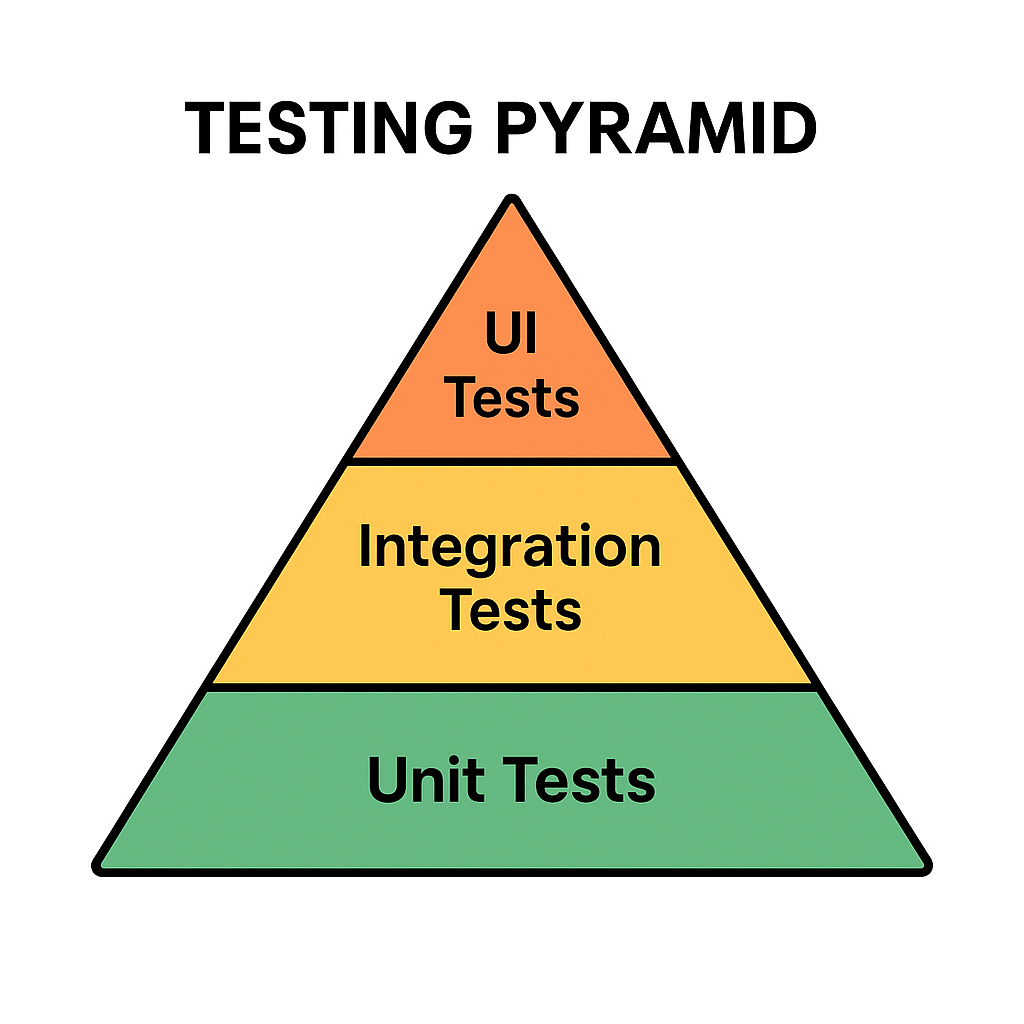

- Deliberate practice: Target a narrow skill (e.g., TDD rhythm, naming, edge-case thinking) and improve it fast.

- Muscle memory for TDD: Red-Green-Refactor becomes automatic under time pressure.

- Design intuition: Frequent refactoring grows your “smell” for better abstractions and simpler designs.

- Safer learning: Fail cheaply in a sandbox instead of production.

- Team alignment: Shared exercises align standards for testing, style, and architecture.

- Confidence & speed: Repetition reduces hesitation; you ship with fewer regressions.

- Interview prep: Katas sharpen fundamentals without “trick” problems.

Main Characteristics (and How to Use Them)

- Small Scope

What it is: A compact problem (30–90 minutes).

How to use: Choose tasks with clear correctness criteria (e.g., string transforms, calculators, parsers). - Repetition & Variation

What it is: Solve the same kata multiple times, adding constraints.

How to use: Repeat weekly; vary approach (different data structures, patterns, or languages). - Time-Boxing

What it is: Short, focused sessions to keep intensity high.

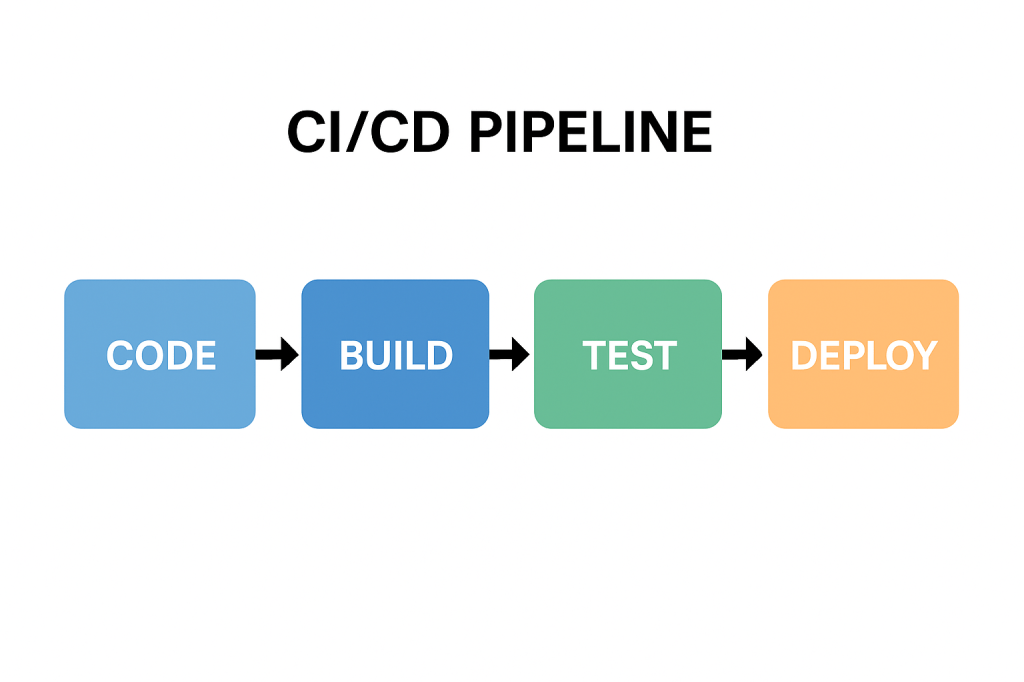

How to use: 25–45 minute blocks (Pomodoro); stop when time ends and reflect. - TDD Rhythm

What it is: Red → Green → Refactor loop.

How to use: Write the smallest failing test, make it pass, then improve the design. Repeat. - Constraints

What it is: Self-imposed rules to sharpen technique.

How to use: Examples: “noifstatements,” “immutable data only,” “only functional style,” “one assert per test.” - Frequent Refactoring

What it is: Continual cleanup to reveal better design.

How to use: After every green step, improve names, extract methods, remove duplication. - Feedback & Reflection

What it is: Short retrospective at the end.

How to use: Capture what slowed you down, smells you saw, patterns you used, and what to try next time. - Social Formats (Dojo/Pair/Mob)

What it is: Practice together.

How to use:- Pair kata: Driver/Navigator switch every 5–7 minutes.

- Mob kata: One keyboard; rotate driver; everyone else reviews and guides.

- Dojo: One person solves while others observe; rotate and discuss.

How to Use Code Katas (Step-by-Step)

- Pick one skill to train (e.g., “fewer conditionals,” “clean tests,” “naming”).

- Choose a kata that fits the skill and your time (30–60 min).

- Set a constraint aligned to your skill (e.g., immutability).

- Run TDD cycles with very small steps; keep tests crisp.

- Refactor relentlessly; remove duplication, clarify intent.

- Stop on time; retrospect (what went well, what to try next).

- Repeat the same kata next week with a new constraint or language.

Real-World Kata Examples (with What They Teach)

- String Calculator

Teaches: TDD rhythm, incremental parsing, edge cases (empty, delimiters, negatives). - Roman Numerals

Teaches: Mapping tables, greedy algorithms, clear tests, refactoring duplication. - Bowling Game Scoring

Teaches: Complex scoring rules, stepwise design, test coverage for tricky cases. - Gilded Rose Refactoring

Teaches: Working with legacy code, characterization tests, safe refactoring. - Mars Rover

Teaches: Command parsing, state modeling, encapsulation, test doubles. - FizzBuzz Variants

Teaches: Simple loops, branching alternatives (lookup tables, rules engines), constraint-driven creativity. - Anagrams / Word Ladder

Teaches: Data structures, performance trade-offs, readability vs speed.

Sample Kata Plan (30 Days)

- Week 1 — TDD Basics: String Calculator (x2), Roman Numerals (x2)

- Week 2 — Refactoring: Gilded Rose (x2), FizzBuzz with constraints (no

if) - Week 3 — Design: Mars Rover (x2), Bowling Game (x2)

- Week 4 — Variation: Repeat two favorites in a new language or paradigm (OO → FP)

Tip: Track each session in a short log: date, kata, constraint, what improved, next experiment.

Team Formats You Can Try

- Lunchtime Dojo (45–60 min): One kata, rotate driver every test.

- Pair Fridays: Everyone pairs; share takeaways at stand-up.

- Mob Monday: One computer; rotate every 5–7 minutes; prioritize learning over finishing.

- Guild Nights: Monthly deep-dives (e.g., legacy refactoring katas).

Common Pitfalls (and Fixes)

- Rushing to “final code” → Fix: Celebrate tiny, green, incremental steps.

- Over-engineering early → Fix: You Aren’t Gonna Need It” (YAGNI). Refactor after tests pass.

- Giant tests → Fix: One behavior per test; clear names; one assert pattern.

- Skipping retros → Fix: Reserve 5 minutes to write notes and choose a new constraint.

Simple Kata Template

Goal: e.g., practice small TDD steps and expressive names

Constraint: e.g., no primitives as method params; use value objects

Time-box: e.g., 35 minutes

Plan:

- Write the smallest failing test for the next slice of behavior.

- Make it pass as simply as possible.

- Refactor names/duplication before the next test.

- Repeat until time ends; then write a short retrospective.

Retrospective Notes (5 min):

- What slowed me down?

- What code smells did I notice?

- What pattern/principle helped?

- What constraint will I try next time?

Example: “String Calculator” (TDD Outline)

- Returns

0for"" - Returns number for single input

"7" - Sums two numbers

"1,2"→3 - Handles newlines

"1\n2,3"→6 - Custom delimiter

"//;\n1;2"→3 - Rejects negatives with message

- Ignores numbers > 1000

- Refactor: extract parser, value object for tokens, clean error handling

When (and When Not) to Use Katas

Use katas when:

- You want to build fluency in testing, refactoring, or design.

- Onboarding a team to shared coding standards.

- Preparing for interviews or new language paradigms.

Avoid katas when:

- You need domain discovery or system design at scale (do spikes instead).

- You’re under a hard delivery deadline—practice sessions shouldn’t cannibalize critical delivery time.

Getting Started (Quick Checklist)

- Pick one kata and one skill to train this week.

- Book two 30–45 minute time-boxes in your calendar.

- Choose a constraint aligned with your skill.

- Practice, then write a short retro.

- Repeat the same kata next week with a variation.

Recent Comments