What is a Unit Test?

A unit test verifies the smallest testable part of your software—usually a single function, method, or class—in isolation. Its goal is to prove that, for a given input, the unit produces the expected output and handles edge cases correctly.

Key characteristics

- Small & fast: millisecond execution, in-memory.

- Isolated: no real network, disk, or database calls.

- Repeatable & deterministic: same input → same result.

- Self-documenting: communicates intended behavior.

A Brief History (How We Got Here)

- 1960s–1980s: Early testing practices emerged with procedural languages, but were largely ad-hoc and manual.

- 1990s: Object-oriented programming popularized more modular designs. Kent Beck introduced SUnit for Smalltalk; the “xUnit” family was born.

- Late 1990s–2000s: JUnit (Java) and NUnit (.NET) pushed unit testing mainstream. Test-Driven Development (TDD) formalized “Red → Green → Refactor.”

- 2010s–today: Rich ecosystems (pytest, Jest, JUnit 5, RSpec, Go’s testing pkg). CI/CD and DevOps turned unit tests into a daily, automated safety net.

How Unit Tests Work (The Mechanics)

Arrange → Act → Assert (AAA)

- Arrange: set up inputs, collaborators (often fakes/mocks).

- Act: call the method under test.

- Assert: verify outputs, state changes, or interactions.

Test Doubles (isolate the unit)

- Dummy: unused placeholders to satisfy signatures.

- Stub: returns fixed data (no behavior verification).

- Fake: lightweight implementation (e.g., in-memory repo).

- Mock: verifies interactions (e.g., method X called once).

- Spy: records calls for later assertions.

Good Test Qualities (FIRST)

- Fast, Isolated, Repeatable, Self-Validating, Timely.

Naming & Structure

- Name:

methodName_condition_expectedResult - One assertion concept per test (clarity > cleverness).

- Avoid coupling to implementation details (test behavior).

When Should We Write Unit Tests?

- New code: ideally before or while coding (TDD).

- Bug fixes: add a unit test that reproduces the bug first.

- Refactors: guard existing behavior before changing code.

- Critical modules: domain logic, calculations, validation.

What not to unit test

- Auto-generated code, trivial getters/setters, framework wiring (unless it encodes business logic).

Advantages (Why Unit Test?)

- Confidence & speed: safer refactors, fewer regressions.

- Executable documentation: shows intended behavior.

- Design feedback: forces smaller, decoupled units.

- Lower cost of defects: catch issues early and cheaply.

- Developer velocity: faster iteration with guardrails.

Practical Examples

Java (JUnit 5 + Mockito)

// src/test/java/com/example/PriceServiceTest.java

import org.junit.jupiter.api.Test;

import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.*;

import static org.mockito.Mockito.*;

class PriceServiceTest {

@Test

void applyDiscount_whenVIP_shouldReduceBy10Percent() {

DiscountPolicy policy = mock(DiscountPolicy.class);

when(policy.discountFor("VIP")).thenReturn(0.10);

PriceService service = new PriceService(policy);

double result = service.applyDiscount(200.0, "VIP");

assertEquals(180.0, result, 0.0001);

verify(policy, times(1)).discountFor("VIP");

}

}

// Production code (for context)

class PriceService {

private final DiscountPolicy policy;

PriceService(DiscountPolicy policy) { this.policy = policy; }

double applyDiscount(double price, String tier) {

return price * (1 - policy.discountFor(tier));

}

}

interface DiscountPolicy { double discountFor(String tier); }

Python (pytest)

# app/discount.py

def apply_discount(price: float, tier: str, policy) -> float:

return price * (1 - policy.discount_for(tier))

# tests/test_discount.py

class FakePolicy:

def discount_for(self, tier):

return {"VIP": 0.10, "STD": 0.0}.get(tier, 0.0)

def test_apply_discount_vip():

from app.discount import apply_discount

result = apply_discount(200.0, "VIP", FakePolicy())

assert result == 180.0

In-Memory Fakes Beat Slow Dependencies

// In-memory repository for fast unit tests

class InMemoryUserRepo implements UserRepo {

private final Map<String, User> store = new HashMap<>();

public void save(User u){ store.put(u.id(), u); }

public Optional<User> find(String id){ return Optional.ofNullable(store.get(id)); }

}

Integrating Unit Tests into Your Current Process

1) Organize Your Project

/src

/main

/java (or /python, /ts, etc.)

/test

/java ...

- Mirror package/module structure under

/test. - Name tests after the unit:

PriceServiceTest,test_discount.py, etc.

2) Make Tests First-Class in CI

GitHub Actions (Java example)

name: build-and-test

on: [push, pull_request]

jobs:

test:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- uses: actions/setup-java@v4

with: { distribution: temurin, java-version: '21' }

- run: ./gradlew test --no-daemon

GitHub Actions (Python example)

name: pytest

on: [push, pull_request]

jobs:

test:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- uses: actions/setup-python@v5

with: { python-version: '3.12' }

- run: pip install -r requirements.txt

- run: pytest -q

3) Define “Done” with Tests

- Pull requests must include unit tests for new/changed logic.

- Code review checklist: readability, edge cases, negative paths.

- Coverage gate (sensible threshold; don’t chase 100%).

Example (Gradle + JaCoCo):

jacocoTestCoverageVerification {

violationRules {

rule { limit { counter = 'INSTRUCTION'; minimum = 0.75 } }

}

}

test.finalizedBy jacocoTestReport, jacocoTestCoverageVerification

4) Keep Tests Fast and Reliable

- Avoid real I/O; prefer fakes/mocks.

- Keep each test < 100ms; whole suite in seconds.

- Eliminate flakiness (random time, real threads, sleeps).

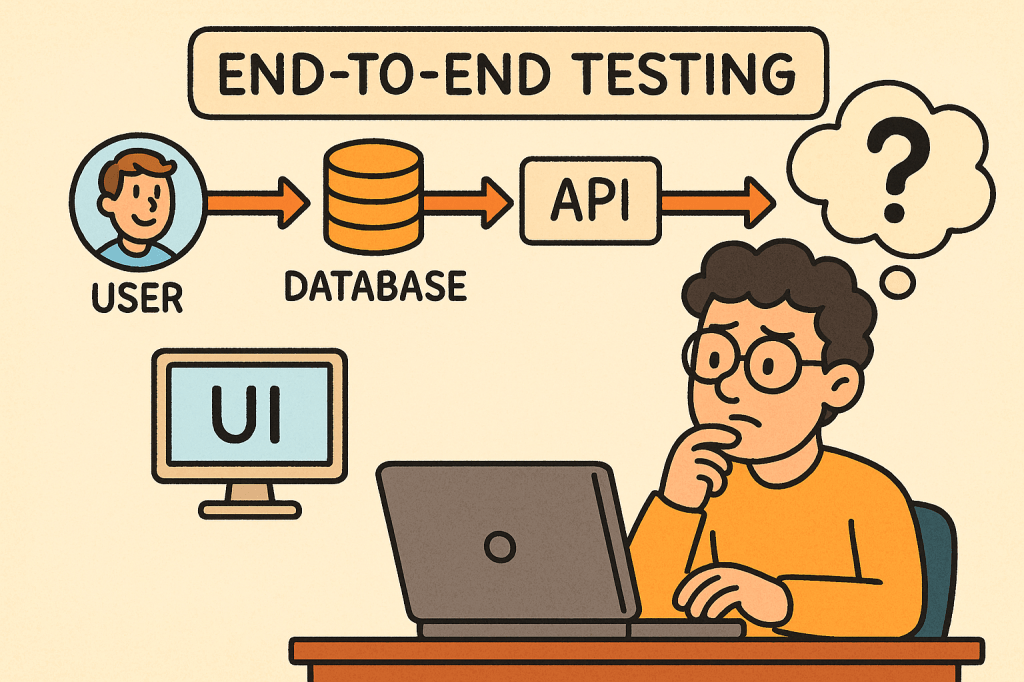

5) Use the Test Pyramid Wisely

- Unit (broad base): thousands, fast, isolated.

- Integration (middle): fewer, verify boundaries.

- UI/E2E (tip): very few, critical user flows only.

A Simple TDD Loop You Can Adopt Tomorrow

- Red: write a failing unit test that expresses the requirement.

- Green: implement the minimum to pass.

- Refactor: clean design safely, keeping tests green.

- Repeat; keep commits small and frequent.

Common Pitfalls (and Fixes)

- Mock-heavy tests that break on refactor → mock only at boundaries; prefer fakes for domain logic.

- Testing private methods → test through public behavior; refactor if testing is too hard.

- Slow suites → remove I/O, shrink fixtures, parallelize.

- Over-asserting → one behavioral concern per test.

Rollout Plan (4 Weeks)

- Week 1: Set up test frameworks, sample tests, CI pipeline, coverage reporting.

- Week 2: Add tests for critical modules & recent bug fixes. Create a PR template requiring tests.

- Week 3: Refactor hot spots guided by tests. Introduce an in-memory fake layer.

- Week 4: Add coverage gates, stabilize the suite, document conventions in

CONTRIBUTING.md.

Team Conventions

- Folder structure mirrors production code.

- Names:

ClassNameTestortest_function_behavior. - AAA layout, one behavior per test.

- No network/disk/DB in unit tests.

- PRs must include tests for changed logic.

Final Thoughts

Unit tests pay dividends by accelerating safe change. Start small, keep them fast and focused, and wire them into your daily workflow (pre-commit, CI, PR reviews). Over time, they become living documentation and your best shield against regressions.

Recent Comments