What is a Queue?

A queue is a fundamental data structure in computer science that follows the FIFO (First In, First Out) principle. This means the first element inserted into the queue will be the first one removed. You can imagine it like a line at a supermarket: the first person who gets in line is the first to be served.

Queues are widely used in software development for managing data in an ordered and controlled way.

Why Do We Need Queues?

Queues are important because they:

- Maintain order of processing.

- Prevent loss of data by ensuring all elements are handled in sequence.

- Support asynchronous operations, such as task scheduling or handling requests.

- Provide a reliable way to manage resources where multiple tasks compete for limited capacity (e.g., printers, processors).

When Should We Use a Queue?

You should consider using a queue when:

- You need to process tasks in the order they arrive (job scheduling, message passing).

- You need a buffer to handle producer-consumer problems (like streaming data).

- You need fair resource sharing (CPU time slicing, printer spooling).

- You’re managing asynchronous workflows, where events need to be handled one by one.

Real World Example

A classic example is a print queue.

When multiple users send documents to a printer, the printer cannot handle them all at once. Instead, documents are placed into a queue. The printer processes the first document added, then moves on to the next, ensuring fairness and order.

Another example is customer service call centers: calls are placed in a queue and answered in the order they arrive.

Time and Memory Complexities

Here’s a breakdown of queue operations:

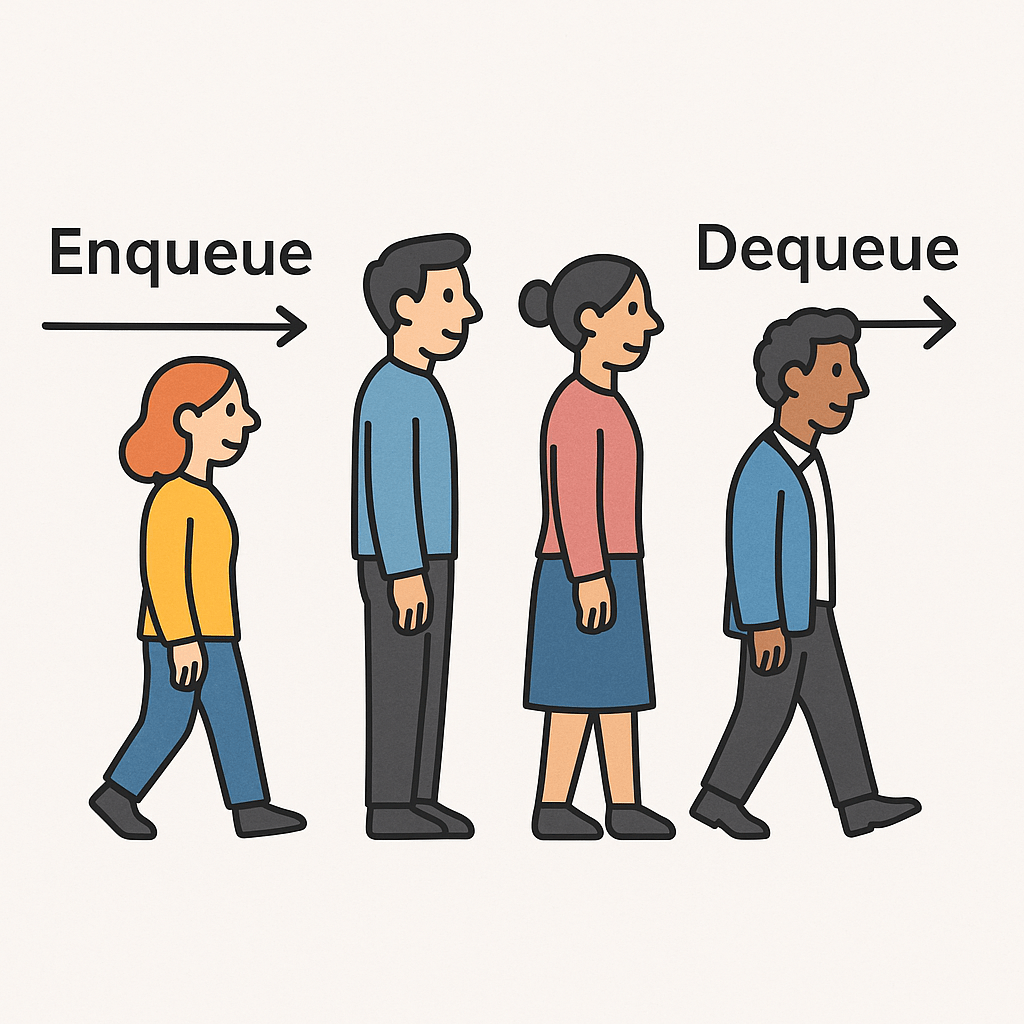

- Enqueue (Insert an element): O(1)

Adding an element at the rear of the queue takes constant time. - Dequeue (Delete an element): O(1)

Removing an element from the front of the queue also takes constant time. - Peek (Access the first element without removing it): O(1)

- Memory Complexity: O(n)

where n is the number of elements currently stored in the queue.

Queues are efficient because insertion and deletion do not require shifting elements (unlike arrays).

Conclusion

Queues are simple yet powerful data structures that help maintain order and efficiency in programming. By applying the FIFO principle, they ensure fairness and predictable behavior in real-world applications such as scheduling, buffering, and resource management.

Mastering queues is essential for every software engineer, as they are a cornerstone of many algorithms and system designs.

Recent Comments