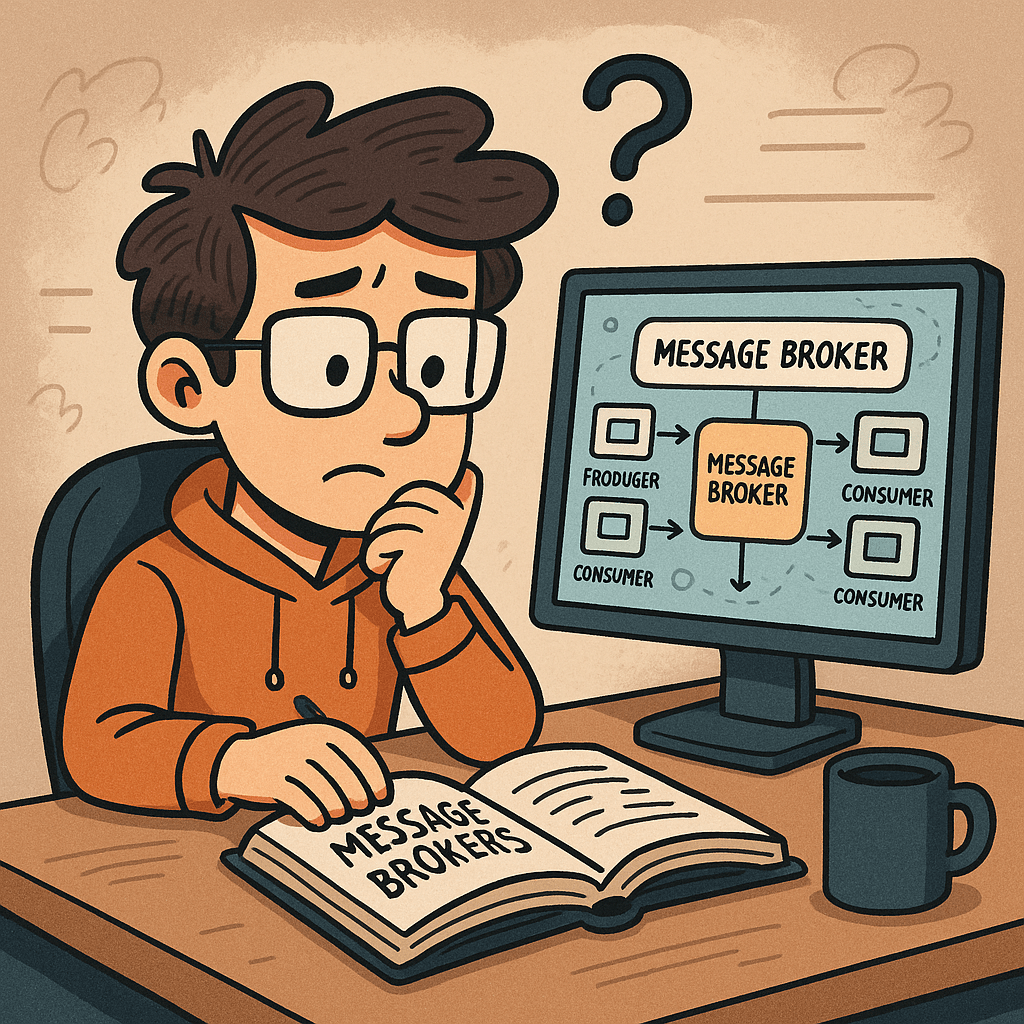

What Is a Message Broker?

A message broker is middleware that routes, stores, and delivers messages between independent parts of a system (services, apps, devices). Instead of services calling each other directly, they publish messages to the broker, and other services consume them. This creates loose coupling, improves resilience, and enables asynchronous workflows.

At its core, a broker provides:

- Producers that publish messages.

- Queues/Topics where messages are held.

- Consumers that receive messages.

- Delivery guarantees and routing so the right messages reach the right consumers.

Common brokers: RabbitMQ, Apache Kafka, ActiveMQ/Artemis, NATS, Redis Streams, AWS SQS/SNS, Google Pub/Sub, Azure Service Bus.

A Short History (High-Level Timeline)

- Mainframe era (1970s–1980s): Early queueing concepts appear in enterprise systems to decouple batch and transactional workloads.

- Enterprise messaging (1990s): Commercial MQ systems (e.g., IBM MQ, Microsoft MSMQ, TIBCO) popularize durable queues and pub/sub for financial and telecom workloads.

- Open standards (late 1990s–2000s): Java Message Service (JMS) APIs and AMQP wire protocol encourage vendor neutrality.

- Distributed streaming (2010s): Kafka and cloud-native services (SQS/SNS, Pub/Sub, Service Bus) emphasize horizontal scalability, event streams, and managed operations.

- Today: Hybrid models—classic brokers (flexible routing, strong per-message semantics) and log-based streaming (high throughput, replayable events) coexist.

How a Message Broker Works (Under the Hood)

- Publish: A producer sends a message with headers and body. Some brokers require a routing key (e.g., “orders.created”).

- Route: The broker uses bindings/rules to deliver messages to the right queue(s) or topic partitions.

- Persist: Messages are durably stored (disk/replicated) according to retention and durability settings.

- Consume: Consumers pull (or receive push-delivered) messages.

- Acknowledge & Retry: On success, the consumer acks; on failure, the broker retries with backoff or moves the message to a dead-letter queue (DLQ).

- Scale: Consumer groups share work (competing consumers). Partitions (Kafka) or multiple queues (RabbitMQ) enable parallelism and throughput.

- Observe & Govern: Metrics (lag, throughput), tracing, and schema/versioning keep systems healthy and evolvable.

Key Features & Characteristics

- Delivery semantics: at-most-once, at-least-once (most common), sometimes exactly-once (with constraints).

- Ordering: per-queue or per-partition ordering; global ordering is rare and costly.

- Durability & retention: in-memory vs disk, replication, time/size-based retention.

- Routing patterns: direct, topic (wildcards), fan-out/broadcast, headers-based, delayed/priority.

- Scalability: horizontal scale via partitions/shards, consumer groups.

- Transactions & idempotency: transactions (broker or app-level), idempotent consumers, deduplication keys.

- Protocols & APIs: AMQP, MQTT, STOMP, HTTP/REST, gRPC; SDKs for many languages.

- Security: TLS in transit, server-side encryption, SASL/OAuth/IAM authN/Z, network policies.

- Observability: consumer lag, DLQ rates, redeliveries, end-to-end tracing.

- Admin & ops: multi-tenant isolation, quotas, quotas per topic, quotas per consumer, cleanup policies.

Main Benefits

- Loose coupling: producers and consumers evolve independently.

- Resilience: retries, DLQs, backpressure protect downstream services.

- Scalability: natural parallelism via consumer groups/partitions.

- Smoothing traffic spikes: brokers absorb bursts; consumers process at steady rates.

- Asynchronous workflows: better UX and throughput (don’t block API calls).

- Auditability & replay: streaming logs (Kafka-style) enable reprocessing and backfills.

- Polyglot interop: cross-language, cross-platform integration via shared contracts.

Real-World Use Cases (With Detailed Flows)

- Order Processing (e-commerce):

- Flow: API receives an order → publishes

order.created. Payment, inventory, shipping services consume in parallel. - Why a broker? Decouples services, enables retries, and supports fan-out to analytics and email notifications.

- Flow: API receives an order → publishes

- Event-Driven Microservices:

- Flow: Services emit domain events (e.g.,

user.registered). Other services react (e.g., create welcome coupon, sync CRM). - Why? Eases cross-team collaboration and reduces synchronous coupling.

- Flow: Services emit domain events (e.g.,

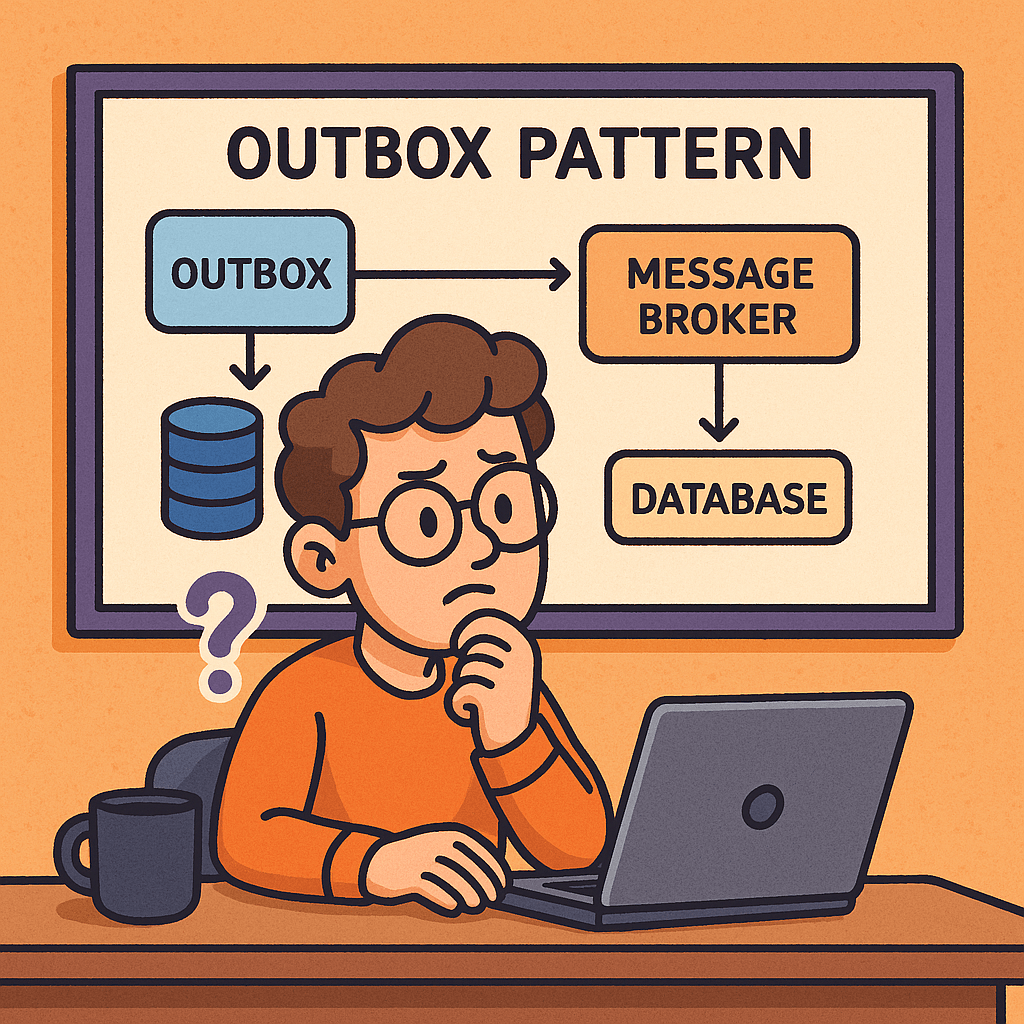

- Transactional Outbox (reliability bridge):

- Flow: Service writes business state and an “outbox” row in the same DB transaction → a relay publishes the event to the broker → exactly-once effect at the boundary.

- Why? Prevents the “saved DB but failed to publish” problem.

- IoT Telemetry & Monitoring:

- Flow: Devices publish telemetry to MQTT/AMQP; backend aggregates, filters, and stores for dashboards & alerts.

- Why? Handles intermittent connectivity, large fan-in, and variable rates.

- Log & Metric Pipelines / Stream Processing:

- Flow: Applications publish logs/events to a streaming broker; processors compute aggregates and feed real-time dashboards.

- Why? High throughput, replay for incident analysis, and scalable consumers.

- Payment & Fraud Detection:

- Flow: Payments emit events to fraud detection service; anomalies trigger holds or manual review.

- Why? Low latency pipelines with backpressure and guaranteed delivery.

- Search Indexing / ETL:

- Flow: Data changes publish “change events” (CDC); consumers update search indexes or data lakes.

- Why? Near-real-time sync without tight DB coupling.

- Notifications & Email/SMS:

- Flow: App publishes

notify.usermessages; a notification service renders templates and sends via providers with retry/DLQ. - Why? Offloads slow/fragile external calls from critical paths.

- Flow: App publishes

Choosing a Broker (Quick Comparison)

| Broker | Model | Strengths | Typical Fits |

|---|---|---|---|

| RabbitMQ | Queues + exchanges (AMQP) | Flexible routing (topic/direct/fanout), per-message acks, plugins | Work queues, task processing, request/reply, multi-tenant apps |

| Apache Kafka | Partitioned log (topics) | Massive throughput, replay, stream processing ecosystem | Event streaming, analytics, CDC, data pipelines |

| ActiveMQ Artemis | Queues/Topics (AMQP, JMS) | Mature JMS support, durable queues, persistence | Java/JMS systems, enterprise integration |

| NATS | Lightweight pub/sub | Very low latency, simple ops, JetStream for persistence | Control planes, lightweight messaging, microservices |

| Redis Streams | Append-only streams | Simple ops, consumer groups, good for moderate scale | Event logs in Redis-centric stacks |

| AWS SQS/SNS | Queue + fan-out | Fully managed, easy IAM, serverless-ready | Cloud/serverless integration, decoupled services |

| GCP Pub/Sub | Topics/subscriptions | Global scale, push/pull, Dataflow tie-ins | GCP analytics pipelines, microservices |

| Azure Service Bus | Queues/Topics | Sessions, dead-lettering, rules | Azure microservices, enterprise workflows |

Integrating a Message Broker Into Your Software Development Process

1) Design the Events and Contracts

- Event storming to find domain events (

invoice.issued,payment.captured). - Define message schema (JSON/Avro/Protobuf) and versioning strategy (backward-compatible changes, default fields).

- Establish routing conventions (topic names, keys/partitions, headers).

- Decide on delivery semantics and ordering requirements.

2) Pick the Broker & Topology

- Match throughput/latency and routing needs to a broker (e.g., Kafka for analytics/replay, RabbitMQ for task queues).

- Plan partitions/queues, consumer groups, and DLQs.

- Choose retention: time/size or compaction (Kafka) to support reprocessing.

3) Implement Producers & Consumers

- Use official clients or proven libs.

- Add idempotency (keys, dedup cache) and exactly-once effects at the application boundary (often via the outbox pattern).

- Implement retries with backoff, circuit breakers, and poison-pill handling (DLQ).

4) Security & Compliance

- Enforce TLS, authN/Z (SASL/OAuth/IAM), least privilege topics/queues.

- Classify data; avoid PII in payloads unless required; encrypt sensitive fields.

5) Observability & Operations

- Track consumer lag, throughput, error rates, redeliveries, DLQ depth.

- Centralize structured logging and traces (correlation IDs).

- Create runbooks for reprocessing, backfills, and DLQ triage.

6) Testing Strategy

- Unit tests for message handlers (pure logic).

- Contract tests to ensure producer/consumer schema compatibility.

- Integration tests using Testcontainers (spin up Kafka/RabbitMQ in CI).

- Load tests to validate partitioning, concurrency, and backpressure.

7) Deployment & Infra

- Provision via IaC (Terraform, Helm).

- Configure quotas, ACLs, retention, and autoscaling.

- Use blue/green or canary deploys for consumers to avoid message loss.

8) Governance & Evolution

- Own each topic/queue (clear team ownership).

- Document schema evolution rules and deprecation process.

- Periodically review retention, partitions, and consumer performance.

Minimal Code Samples (Spring Boot, so you can plug in quickly)

Kafka Producer (Spring Boot)

@Service

public class OrderEventProducer {

private final KafkaTemplate<String, String> kafka;

public OrderEventProducer(KafkaTemplate<String, String> kafka) {

this.kafka = kafka;

}

public void publishOrderCreated(String orderId, String payloadJson) {

kafka.send("orders.created", orderId, payloadJson); // use orderId as key for ordering

}

}

Kafka Consumer

@Component

public class OrderEventConsumer {

@KafkaListener(topics = "orders.created", groupId = "order-workers")

public void onMessage(String payloadJson) {

// TODO: validate schema, handle idempotency via orderId, process safely, log traceId

}

}

RabbitMQ Consumer (Spring AMQP)

@Component

public class EmailConsumer {

@RabbitListener(queues = "email.notifications")

public void handleEmail(String payloadJson) {

// Render template, call provider with retries; nack to DLQ on poison messages

}

}

Docker Compose (Local Dev)

services:

rabbitmq:

image: rabbitmq:3-management

ports: ["5672:5672", "15672:15672"] # UI at :15672

kafka:

image: bitnami/kafka:latest

environment:

- KAFKA_ENABLE_KRAFT=yes

- KAFKA_CFG_AUTO_CREATE_TOPICS_ENABLE=true

ports: ["9092:9092"]

Common Pitfalls (and How to Avoid Them)

- Treating the broker like a database: keep payloads small, use a real DB for querying and relationships.

- No schema discipline: enforce contracts; add fields in backward-compatible ways.

- Ignoring DLQs: monitor and drain with runbooks; fix root causes, don’t just requeue forever.

- Chatty synchronous RPC over MQ: use proper async patterns; when you must do request-reply, set timeouts and correlation IDs.

- Hot partitions: choose balanced keys; consider hashing or sharding strategies.

A Quick Integration Checklist

- Pick broker aligned to throughput/routing needs.

- Define topic/queue naming, keys, and retention.

- Establish message schemas + versioning rules.

- Implement idempotency and the transactional outbox where needed.

- Add retries, backoff, and DLQ policies.

- Secure with TLS + auth; restrict ACLs.

- Instrument lag, errors, DLQ depth, and add tracing.

- Test with Testcontainers in CI; load test for spikes.

- Document ownership and runbooks for reprocessing.

- Review partitions/retention quarterly.

Final Thoughts

Message brokers are a foundational building block for event-driven, resilient, and scalable systems. Start by modeling the events and delivery guarantees you need, then select a broker that fits your routing and throughput profile. With solid schema governance, idempotency, DLQs, and observability, you’ll integrate messaging into your development process confidently—and unlock patterns that are hard to achieve with synchronous APIs alone.

Recent Comments