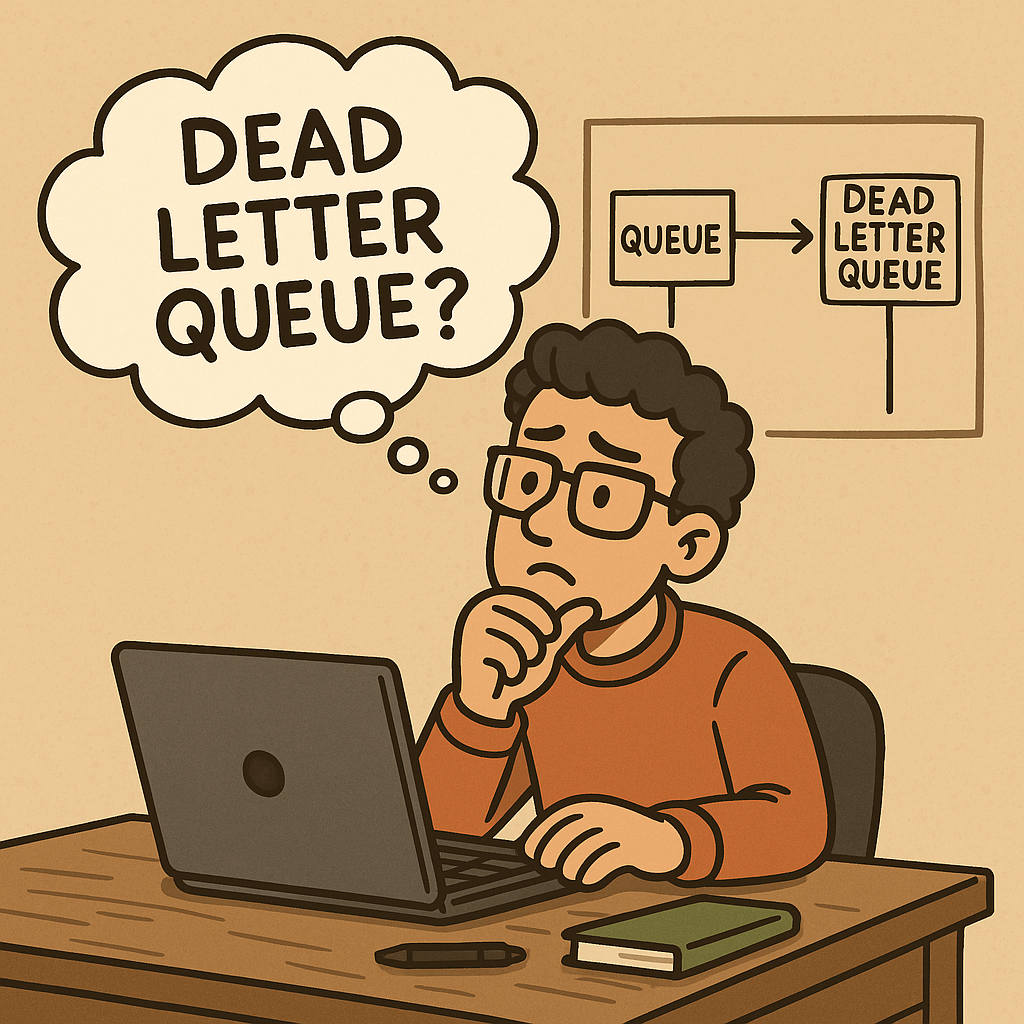

A Dead Letter Queue (DLQ) is a dedicated queue where messages go when your system can’t process them successfully after a defined number of retries or due to validation/format issues. DLQs prevent poison messages from blocking normal traffic, preserve data for diagnostics, and give you a safe workflow to fix and reprocess failures.

What Is a Dead Letter Queue?

A Dead Letter Queue (DLQ) is a secondary queue linked to a primary “work” queue (or topic subscription). When a message repeatedly fails processing—or violates rules like TTL, size, or schema—it’s moved to the DLQ instead of being retried forever or discarded.

Key idea: separate bad/problematic messages from the healthy stream so the system stays reliable and debuggable.

How Does It Work? (Step by Step)

1) Message arrives

- Producer publishes a message to the main queue/topic.

- The message includes metadata (headers) like correlation ID, type, version, and possibly a retry counter.

2) Consumer processes

- Your worker/service reads the message and attempts business logic.

- If successful → ACK/NACK appropriately → message is removed.

3) Failure and retries

- If processing fails (e.g., validation error, missing dependency, transient DB outage), the consumer either NACKs or throws an error.

- Broker policy or your code triggers a retry (immediate or delayed/exponential backoff).

4) Dead-lettering policy

- When a threshold is met (e.g.,

maxReceiveCount = 5, or message TTL exceeded, or explicitly rejected as “unrecoverable”), the broker moves the message to the DLQ. - The DLQ carries the original payload plus broker-specific reason codes and delivery attempt metadata.

5) Inspection and reprocessing

- Operators/engineers inspect DLQ messages, identify root cause, fix code/data/config, and then reprocess messages from the DLQ back into the main flow (or a special “retry” queue).

Benefits & Advantages (Why DLQs Matter)

1) Reliability and throughput protection

- Poison messages don’t block the main queue, so healthy traffic continues to flow.

2) Observability and forensics

- You don’t lose failed messages: you can explain failures, reproduce bugs, and perform root-cause analysis.

3) Controlled recovery

- You can reprocess failed messages in a safe, rate-limited way after fixes, reducing blast radius.

4) Compliance and auditability

- DLQs preserve evidence of failures (with timestamps and reason codes), useful for audits and postmortems.

5) Cost and performance balance

- By cutting infinite retries, you reduce wasted compute and noisy logs.

When and How Should We Use a DLQ?

Use a DLQ when…

- Messages can be malformed, out-of-order, or schema-incompatible.

- Downstream systems are occasionally unavailable or rate-limited.

- You operate at scale and need protection from poison messages.

- You must keep evidence of failures for audit/compliance.

How to configure (common patterns)

- Set a retry cap: e.g., 3–10 attempts with exponential backoff.

- Define dead-letter conditions: max attempts, TTL expiry, size limit, explicit rejection.

- Include reason metadata: error codes, stack traces (trimmed), last-failure timestamp.

- Create a reprocessing path: tooling or jobs to move messages back after fixes.

Main Challenges (and How to Handle Them)

1) DLQ becoming a “graveyard”

- Risk: Messages pile up and are never reprocessed.

- Mitigation: Ownership, SLAs, on-call runbooks, weekly triage, dashboards, and auto-alerts.

2) Distinguishing transient vs. permanent failures

- Risk: You keep retrying messages that will never succeed.

- Mitigation: Classify errors (e.g., 5xx transient vs. 4xx permanent), and dead-letter permanent failures early.

3) Message evolution & schema drift

- Risk: Older messages don’t match new contracts.

- Mitigation: Use schema versioning, backward-compatible serializers (e.g., Avro/JSON with defaults), and upconverters.

4) Idempotency and duplicates

- Risk: Reprocessing may double-charge or double-ship.

- Mitigation: Idempotent handlers keyed by message ID/correlation ID; dedupe storage.

5) Privacy & retention

- Risk: Sensitive data lingers in DLQ.

- Mitigation: Redact PII fields, encrypt at rest, set retention policies, purge according to compliance.

6) Operational toil

- Risk: Manual replays are slow and error-prone.

- Mitigation: Provide a self-serve DLQ UI/CLI, canned filters, bulk reprocess with rate limits.

Real-World Examples (Deep Dive)

Example 1: E-commerce order workflow (Kafka/RabbitMQ/Azure Service Bus)

- Scenario: Payment service consumes

OrderPlacedevents. A small percentage fails due to expired cards or unknown currency. - Flow:

- Consumer validates schema and payment method.

- For transient payment gateway outages → retry with exponential backoff (e.g., 1m, 5m, 15m).

- For permanent issues (invalid currency) → send directly to DLQ with reason

UNSUPPORTED_CURRENCY. - Weekly DLQ triage: finance reviews messages, fixes catalog currency mappings, then reprocesses only the corrected subset.

Example 2: Logistics tracking updates (AWS SQS)

- Scenario: IoT devices send GPS updates. Rare firmware bug emits malformed JSON.

- Flow:

- SQS main queue with

maxReceiveCount=5. - Malformed messages fail schema validation 5× → moved to DLQ.

- An ETL “scrubber” tool attempts to auto-fix known format issues; successful ones are re-queued; truly bad ones are archived and reported.

- SQS main queue with

Example 3: Billing invoice generation (GCP Pub/Sub)

- Scenario: Monthly invoice generation fan-out; occasionally the customer record is missing tax info.

- Flow:

- Pub/Sub subscription push to worker; on 4xx validation error, message is acknowledged to prevent infinite retries and manually published to a DLQ topic with reason

MISSING_TAX_PROFILE. - Ops runs a batch to fetch missing tax profiles; after remediation, a replay job re-emits those messages to a “retry” topic at a safe rate.

- Pub/Sub subscription push to worker; on 4xx validation error, message is acknowledged to prevent infinite retries and manually published to a DLQ topic with reason

Broker-Specific Notes (Quick Reference)

- AWS SQS: Configure a redrive policy linking main queue to DLQ with

maxReceiveCount. Use CloudWatch metrics/alarms onApproximateNumberOfMessagesVisiblein the DLQ. - Amazon SNS → SQS: DLQ typically sits behind the SQS subscription. Each subscription can have its own DLQ.

- Azure Service Bus: DLQs exist per queue and per subscription. Service Bus auto-dead-letters on TTL, size, or filter issues; you can explicitly dead-letter via SDK.

- Google Pub/Sub: No first-class DLQ historically; implement via a dedicated “dead-letter topic” plus subscriber logic (Pub/Sub now supports dead letter topics on subscriptions—set

deadLetterPolicywith max delivery attempts). - RabbitMQ: Use alternate exchange or per-queue dead-letter exchange (DLX) with dead-letter routing keys; create a bound DLQ queue that receives rejected/expired messages.

Integration Guide: Add DLQs to Your Development Process

1) Design a DLQ policy

- Retry budget:

max_attempts = 5, backoff1m → 5m → 15m → 1h → 6h(example). - Classify failures:

- Transient (timeouts, 5xx): retry up to budget.

- Permanent (validation, 4xx): dead-letter immediately.

- Metadata to include: correlation ID, producer service, schema version, last error code/reason, first/last failure timestamps.

2) Implement idempotency

- Use a processing log keyed by message ID; ignore duplicates.

- For stateful side effects (e.g., billing), store an idempotency key and status.

3) Add observability

- Dashboards: DLQ depth, inflow rate, age percentiles (P50/P95), reasons top-N.

- Alerts: when DLQ depth or age exceeds thresholds; when a single reason spikes.

4) Build safe reprocessing tools

- Provide a CLI/UI to:

- Filter by reason code/time window/producer.

- Bulk requeue with rate limits and circuit breakers.

- Simulate dry-run processing (validation-only) before replay.

5) Automate triage & ownership

- Assign service owners for each DLQ.

- Weekly scheduled triage with an SLA (e.g., “no DLQ message older than 7 days”).

- Tag JIRA tickets with DLQ reason codes.

6) Security & compliance

- Redact PII in payloads or keep PII in secure references.

- Set retention (e.g., 14–30 days) and auto-archive older messages to encrypted object storage.

Practical Config Snippets (Pseudocode)

Retry + Dead-letter decision (consumer)

onMessage(msg):

try:

validateSchema(msg)

processBusinessLogic(msg)

ack(msg)

except TransientError as e:

if msg.attempts < MAX_ATTEMPTS:

requeueWithDelay(msg, backoffFor(msg.attempts))

else:

sendToDLQ(msg, reason="RETRY_BUDGET_EXCEEDED", error=e.summary)

except PermanentError as e:

sendToDLQ(msg, reason="PERMANENT_VALIDATION_FAILURE", error=e.summary)

Idempotency guard

if idempotencyStore.exists(msg.id):

ack(msg) # already processed

else:

result = handle(msg)

idempotencyStore.record(msg.id, result.status)

ack(msg)

Operational Runbook (What to Do When DLQ Fills Up)

- Check dashboards: DLQ depth, top reasons.

- Classify spike: deployment-related? upstream schema change? dependency outage?

- Fix root cause: roll back, hotfix, or add upconverter/validator.

- Sample messages: inspect payloads; verify schema/PII.

- Dry-run replay: validate-only path over a small batch.

- Controlled replay: requeue with rate limit (e.g., 50 msg/s) and monitor error rate.

- Close the loop: add tests, update schemas, document the incident.

Metrics That Matter

- DLQ Depth (current and trend)

- Message Age in DLQ (P50/P95/max)

- DLQ Inflow/Outflow Rate

- Top Failure Reasons (by count)

- Replay Success Rate

- Time-to-Remediate (first seen → replayed)

FAQ

Is a DLQ the same as a retry queue?

No. A retry queue is for delayed retries; a DLQ is for messages that exhausted retry policy or are permanently invalid.

Should every queue have a DLQ?

For critical paths—yes. For low-value or purely ephemeral events, weigh the operational cost vs. benefit.

Can we auto-delete DLQ messages?

You should set retention, but avoid blind deletion. Consider archiving with limited retention to support audits.

Checklist: Fast DLQ Implementation

- DLQ created and linked to each critical queue/subscription

- Retry policy set (max attempts + exponential backoff)

- Error classification (transient vs permanent)

- Idempotency implemented

- Dashboards and alerts configured

- Reprocessing tool with rate limits

- Ownership & triage cadence defined

- Retention, redaction, and encryption reviewed

Conclusion

A well-implemented DLQ is your safety net for message-driven systems: it safeguards throughput, preserves evidence, and enables controlled recovery. With clear policies, observability, and a disciplined replay workflow, DLQs transform failures from outages into actionable insights—and keep your pipelines resilient.

Recent Comments