What is a Conflict-free Replicated Data Type?

A Conflict-free Replicated Data Type (CRDT) is a data structure that allows multiple computers or systems to update shared data independently and concurrently without requiring coordination. Even if updates happen in different orders across different replicas, CRDTs guarantee that all copies of the data will eventually converge to the same state.

In simpler terms, CRDTs make it possible to build distributed systems (like collaborative applications) where users can work offline, make changes, and later sync with others without worrying about conflicts.

A Brief History of CRDTs

The concept of CRDTs emerged in the late 2000s when researchers in distributed computing began looking for alternatives to traditional locking and consensus mechanisms. Traditional approaches like Paxos or Raft ensure consistency but often come with performance trade-offs and complex coordination.

CRDTs were formally introduced around 2011 by Marc Shapiro and his team, who proposed them as a solution for eventual consistency in distributed systems. Since then, CRDTs have been widely researched and adopted in real-world applications such as collaborative editors, cloud storage, and messaging systems.

How Do CRDTs Work?

CRDTs are designed around two main principles:

- Local Updates Without Coordination

Each replica of the data can be updated independently, even while offline. - Automatic Conflict Resolution

Instead of requiring external conflict resolution, CRDTs are mathematically designed so that when updates are merged, the data structure always converges to the same state.

They achieve this by relying on mathematical properties like commutativity (order doesn’t matter) and idempotence (repeating an operation has no negative effect).

Benefits of CRDTs

- No Conflicts: Updates never conflict; they are automatically merged.

- Offline Support: Applications can work offline and sync later.

- High Availability: Since coordination isn’t required for each update, systems remain responsive even in cases of network partitions.

- Scalability: Suitable for large-scale distributed applications because they reduce synchronization overhead.

Types of CRDTs

CRDTs come in two broad categories: Operation-based and State-based.

1. State-based CRDTs (Convergent Replicated Data Types)

- Each replica periodically sends its entire state to others.

- The states are merged using a mathematical function that ensures convergence.

- Example: G-Counter (Grow-only Counter).

2. Operation-based CRDTs (Commutative Replicated Data Types)

- Instead of sending full states, replicas send the operations (like “add 1” or “insert character”) to others.

- Operations are designed so that they commute (order doesn’t matter).

- Example: PN-Counter (Positive-Negative Counter).

Common CRDT Structures

- Counters

- G-Counter: Only increases. Useful for counting events.

- PN-Counter: Can increase and decrease.

- Registers

- Stores a single value.

- Last-Write-Wins Register resolves conflicts by picking the latest update based on timestamps.

- Sets

- G-Set (Grow-only Set): Items can only be added.

- 2P-Set (Two-Phase Set): Items can be added and removed, but once removed, cannot be re-added.

- OR-Set (Observed-Removed Set): Allows both adds and removes with better flexibility.

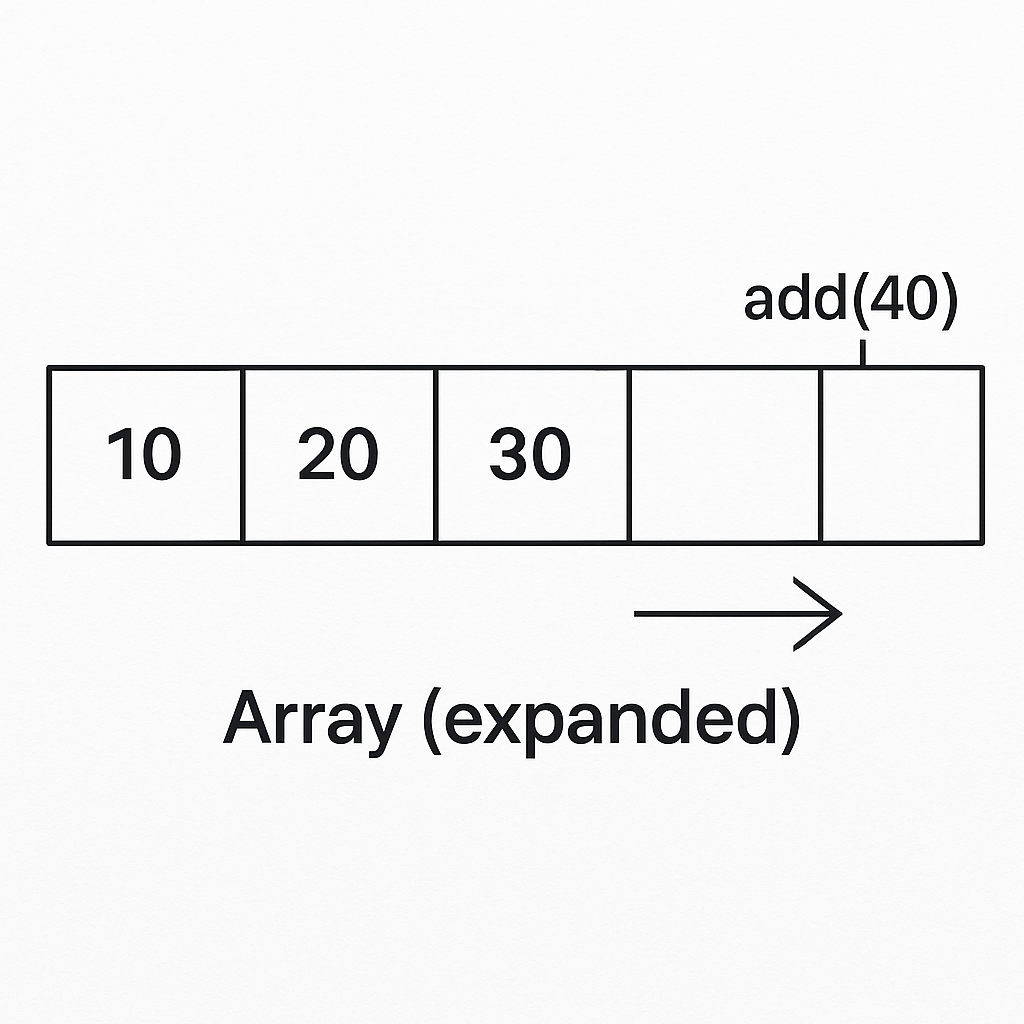

- Sequences

- Used in collaborative text editing where multiple users edit documents simultaneously.

- Example: RGA (Replicated Growable Array) or LSEQ.

- Maps

- A dictionary-like structure where keys map to CRDT values (counters, sets, etc.).

Real-World Use Cases of CRDTs

- Collaborative Document Editing: Google Docs, Microsoft Office Online, and other real-time editors use CRDT-like concepts to merge changes from multiple users.

- Messaging Apps: WhatsApp and Signal use CRDT principles for message synchronization across devices.

- Distributed Databases: Databases like Riak and Redis (with CRDT extensions) implement them for high availability.

- Cloud Storage: Systems like Dropbox and OneDrive rely on CRDTs to merge offline file edits.

When and How Should We Use CRDTs?

When to Use

- Applications that require real-time collaboration (text editors, shared whiteboards).

- Messaging platforms that need to handle offline delivery and sync.

- Distributed systems where network failures are common but consistency is still required.

- IoT systems where devices may work offline but sync data later.

How to Use

- Choose the right CRDT type (counter, set, register, map, or sequence) depending on your use case.

- Integrate CRDT libraries available for your programming language (e.g., Automerge in JavaScript, Riak’s CRDT support in Erlang, or Akka Distributed Data in Scala/Java).

- Design your application around eventual consistency rather than strict, immediate consistency.

Conclusion

Conflict-free Replicated Data Types (CRDTs) are powerful tools for building modern distributed applications that require collaboration, offline support, and high availability. With their mathematically guaranteed conflict resolution, they simplify the complexity of distributed data synchronization.

If you’re building an app where multiple users interact with the same data—whether it’s text editing, messaging, or IoT data collection—CRDTs might be the right solution.

Recent Comments