What is a One-Time Password?

A One-Time Password (OTP) is a code (e.g., 6–8 digits) that’s valid for a single use and typically expires quickly (e.g., 30–60 seconds). OTPs are used to:

- Strengthen login (as a second factor, MFA)

- Approve sensitive actions (step-up auth)

- Validate contact points (phone/email ownership)

- Reduce fraud in payment or money movement flows

OTPs may be:

- TOTP: time-based, generated locally in an authenticator app (e.g., 6-digit code rotating every 30s)

- HOTP: counter-based, generated from a moving counter value

- Out-of-band: delivered via SMS, email, or push (server sends the code out through another channel)

A Brief History (S/Key → HOTP → TOTP → Modern MFA)

- 1981: Leslie Lamport introduces the concept of one-time passwords using hash chains.

- 1990s (S/Key / OTP): Early challenge-response systems popularize one-time codes derived from hash chains (RFC 1760, later RFC 2289).

- 2005 (HOTP, RFC 4226): Standardizes HMAC-based One-Time Password using a counter; each next code increments a counter.

- 2011 (TOTP, RFC 6238): Standardizes Time-based OTP by replacing counter with time steps (usually 30 seconds), enabling app-based codes (Google Authenticator, Microsoft Authenticator, etc.).

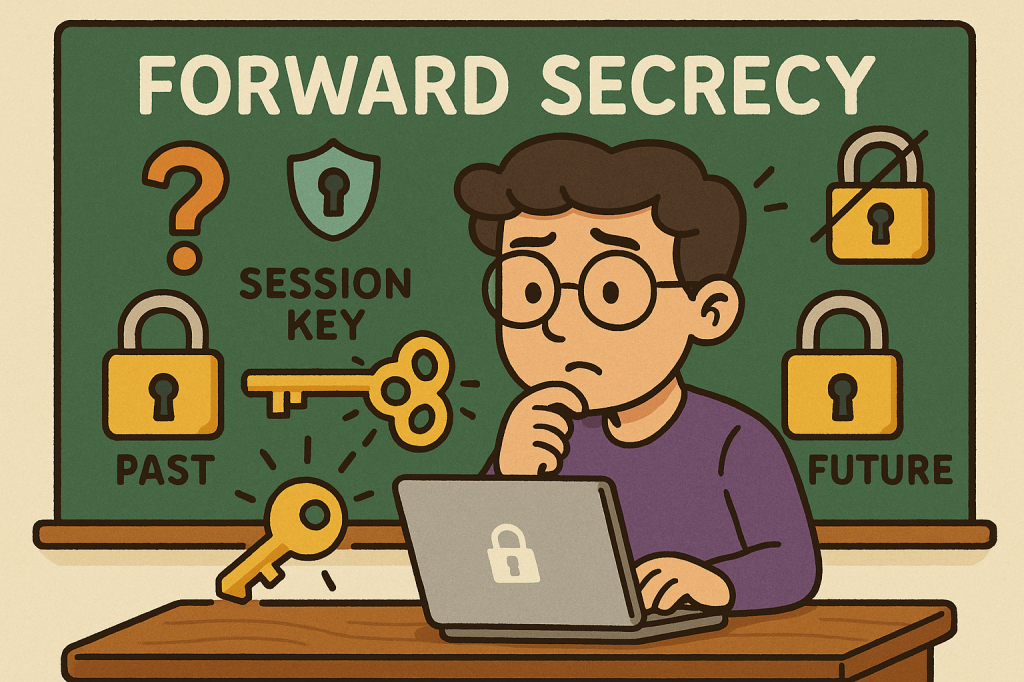

- 2010s–present: OTP becomes a mainstream second factor. The ecosystem expands with push approvals, number matching, device binding, and WebAuthn (which offers phishing-resistant MFA; OTP still widely used for reach and familiarity).

How OTP Works (with step-by-step flows)

1. TOTP (Time-based One-Time Password)

Idea: Client and server share a secret key. Every 30 seconds, both compute a new code from the secret + current time.

Generation (client/app):

- Determine current Unix time

t. - Compute time step

T = floor(t / 30). - Compute

HMAC(secret, T)(e.g., HMAC-SHA-1/256). - Dynamic truncate to 31-bit integer, then mod

10^digits(e.g., 10^6 → 6 digits). - Display code like

413 229(expires when the 30-second window rolls).

Verification (server):

- Recompute expected codes for

Tplus a small window (e.g., T-1, T, T+1) to tolerate clock skew. - Compare user-entered code with any expected code.

- Enforce rate limiting and replay protection.

2. HOTP (Counter-based One-Time Password)

Idea: Instead of time, use a counter that increments on each code generation.

Generation: HMAC(secret, counter) → truncate → mod 10^digits.

Verification: Server allows a look-ahead window to resynchronize if client counters drift.

3. Out-of-Band Codes (SMS/Email/Push)

Idea: Server creates a random code and sends it through a side channel (e.g., SMS).

Verification: User types the received code; server checks match and expiration.

Pros: No app install; broad reach.

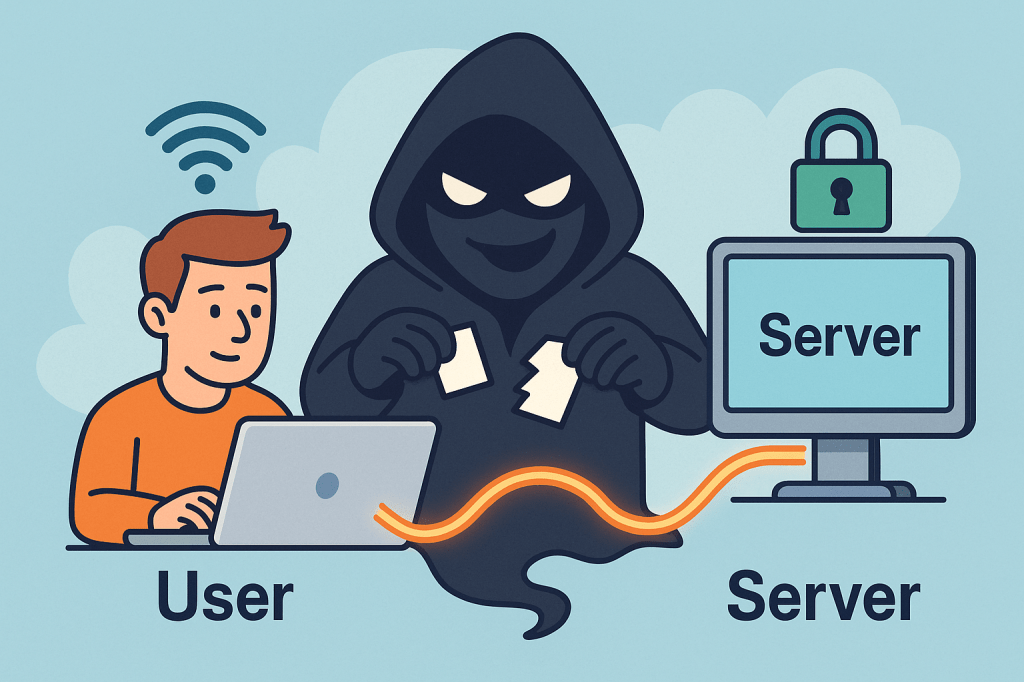

Cons: Vulnerable to SIM swap, SS7 weaknesses, email compromise, and phishing relays.

Core Components of an OTP System

- Shared Secret (TOTP/HOTP): A per-user secret key (e.g., Base32) provisioned via QR code/URI during enrollment.

- Code Generator:

- Client-side (authenticator app) for TOTP/HOTP

- Server-side generator for out-of-band codes

- Delivery Channel: SMS, email, or push (for out-of-band); not needed for app-based TOTP/HOTP.

- Verifier Service: Validates codes with timing/counter windows, rate limits, and replay detection.

- Secure Storage: Store secrets with strong encryption and access controls (e.g., HSM or KMS).

- Enrollment & Recovery: QR provisioning, backup codes, device change/reset flows.

- Observability & Risk Engine: Logging, anomaly detection, geo/behavioral checks, adaptive step-up.

Benefits of Using OTP

- Stronger security than passwords alone (defends against password reuse and basic credential stuffing).

- Low friction & low cost (especially TOTP apps—no per-SMS fees).

- Offline capability (TOTP works without network on the user device).

- Standards-based & interoperable (HOTP/TOTP widely supported).

- Flexible use cases: MFA, step-up approvals, transaction signing, device verification.

Weaknesses & Common Attacks

- Phishing & Real-Time Relay: Attackers proxy login, capturing OTP and replaying instantly.

- SIM Swap / SS7 Issues (SMS OTP): Phone number hijacking allows interception of SMS codes.

- Email Compromise: If email is breached, emailed OTPs are exposed.

- Malware/Overlays on Device: Can exfiltrate TOTP codes or intercept out-of-band messages.

- Shared-Secret Risks: Poor secret handling during provisioning/storage leaks all future codes.

- Clock Drift (TOTP): Device/server time mismatch causes false rejects.

- Brute-force Guessing: Short codes require strict rate limiting and lockouts.

- Usability & Recovery Gaps: Device loss without backup codes locks users out.

Note: OTP improves security but is not fully phishing-resistant. For high-risk scenarios, pair with phishing-resistant MFA (e.g., WebAuthn security keys or device-bound passkeys) and/or number-matching push.

When and How Should You Use OTP?

Use OTP when:

- Adding MFA to protect accounts with moderate to high value.

- Performing step-up auth for sensitive actions (password change, wire transfer).

- Validating contact channels (phone/email ownership).

- Operating offline contexts (TOTP works without data).

Choose the method:

- TOTP app (recommended default): secure, cheap, offline, broadly supported.

- SMS/email OTP: maximize reach; acceptable for low/medium risk with compensating controls.

- Push approvals with number matching: good UX and better phishing defenses than raw OTP entry.

- HOTP: niche, but useful for hardware tokens or counter-based devices.

Integration Guide for Your Software Development Lifecycle

1. Architecture Overview

- Backend: OTP service (issue/verify), secret vault/KMS, rate limiter, audit logs.

- Frontend: Enrollment screens (QR), verification forms, recovery/backup code flows.

- Delivery (optional): SMS/email provider, push service.

- Risk & Observability: Metrics, alerts, anomaly detection.

2. Enrollment Flow (TOTP)

- Generate a random per-user secret (160–256 bits).

- Store encrypted; never log secrets.

- Show otpauth:// URI as a QR code (issuer, account name, algorithm, digits, period).

- Ask user to type the current app code to verify setup.

- Issue backup codes; prompt to save securely.

3. Verification Flow (TOTP)

- User enters 6-digit code.

- Server recomputes expected codes for

T-1..T+1. - If match → success; else increment rate-limit counters and show safe errors.

- Log event and update risk signals.

4. Out-of-Band OTP Flow (SMS/Email)

- Server creates a random code (e.g., 6–8 digits), stores hash + expiry (e.g., 5 min).

- Send via chosen channel; avoid secrets in message templates.

- Verify user input; invalidate on success; limit attempts.

5. Code Examples (Quick Starts)

Java (Spring Security + TOTP using java-time + any TOTP lib):

// Pseudocode: verify TOTP code for user

boolean verifyTotp(String base32Secret, int userCode, long nowEpochSeconds) {

long timeStep = 30;

long t = nowEpochSeconds / timeStep;

for (long offset = -1; offset <= 1; offset++) {

int expected = Totp.generate(base32Secret, t + offset); // lib call

if (expected == userCode) return true;

}

return false;

}

Node.js (TOTP with otplib or speakeasy):

const { authenticator } = require('otplib');

authenticator.options = { step: 30, digits: 6 }; // default

const isValid = authenticator.verify({

token: userInput,

secret: base32Secret

});

Python (pyotp):

import pyotp, time

totp = pyotp.TOTP(base32_secret, interval=30, digits=6)

is_valid = totp.verify(user_input, valid_window=1) # allow ±1 step

6. Data Model & Storage

user_id,otp_type(TOTP/HOTP/SMS/email),secret_ref(KMS handle),enrolled_at,revoked_at- For out-of-band:

otp_hash,expires_at,attempts,channel,destination_masked - Never store raw secrets or raw sent codes; store hash + salt for generated codes.

7. DevOps & Config

- Secrets in KMS/HSM; rotate issuer keys periodically.

- Rate limits: attempts per minute/hour/day; IP + account scoped.

- Alerting: spikes in failures, drift errors, provider delivery issues.

- Feature flags to roll out MFA gradually and enforce for riskier cohorts.

UX & Security Best Practices

- Promote app-based TOTP over SMS/email by default; offer SMS/email as fallback.

- Number matching for push approvals to mitigate tap-yes fatigue.

- Backup codes: one-time printable set; show only on enrollment; allow regen with step-up.

- Device time checks: prompt users if the clock is off; provide NTP sync tips.

- Masked channels: show

•••-•••-1234rather than full phone/email. - Progressive enforcement: warn first, then require OTP for risky events.

- Anti-phishing: distinguish trusted UI (e.g., app domain, passkeys), consider origin binding and link-proofing.

- Accessibility & i18n: voice, large text, copy/paste, code grouping

123-456.

Testing & Monitoring Checklist

Functional

- TOTP verification with ±1 step window

- SMS/email resend throttling and code invalidation

- Backup codes (single use)

- Enrollment verification required before enablement

Security

- Secrets stored via KMS/HSM; no logging of secrets/codes

- Brute-force rate limits + exponential backoff

- Replay protection (invalidate out-of-band codes on success)

- Anti-automation (CAPTCHA/behavioral) where appropriate

Reliability

- SMS/email provider failover or graceful degradation

- Clock drift alarm; NTP health

- Dashboards: success rate, latency, delivery failure, fraud signals

Glossary

- OTP: One-Time Password—single-use code for auth or approvals.

- HOTP (RFC 4226): HMAC-based counter-driven OTP.

- TOTP (RFC 6238): Time-based OTP—rotates every fixed period (e.g., 30s).

- MFA: Multi-Factor Authentication—two or more independent factors.

- Step-Up Auth: Extra verification for high-risk actions.

- Number Matching: Push approval shows a code the user must match, deterring blind approval.

- WebAuthn/Passkeys: Phishing-resistant MFA based on public-key cryptography.

Final Thoughts

OTP is a powerful, standards-backed control that significantly raises the bar for attackers—if you implement it well. Prefer TOTP apps for security and cost, keep SMS/email for reach with compensating controls, and plan a path toward phishing-resistant options (WebAuthn) for your most sensitive use cases.

Recent Comments