What is Dependency Injection?

Dependency Injection (DI) is a design pattern in software engineering where the dependencies of a class or module are provided from the outside, rather than being created internally. In simpler terms, instead of a class creating the objects it needs, those objects are “injected” into it. This approach decouples components, making them more flexible, testable, and maintainable.

For example, instead of a class instantiating a database connection itself, the connection object is passed to it. This allows the class to work with different types of databases without changing its internal logic.

A Brief History of Dependency Injection

The concept of Dependency Injection has its roots in the Inversion of Control (IoC) principle, which was popularized in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Martin Fowler formally introduced the term “Dependency Injection” in 2004, describing it as a way to implement IoC. Frameworks like Spring (Java) and later .NET Core made DI a first-class citizen in modern software development, encouraging developers to separate concerns and write loosely coupled code.

Main Components of Dependency Injection

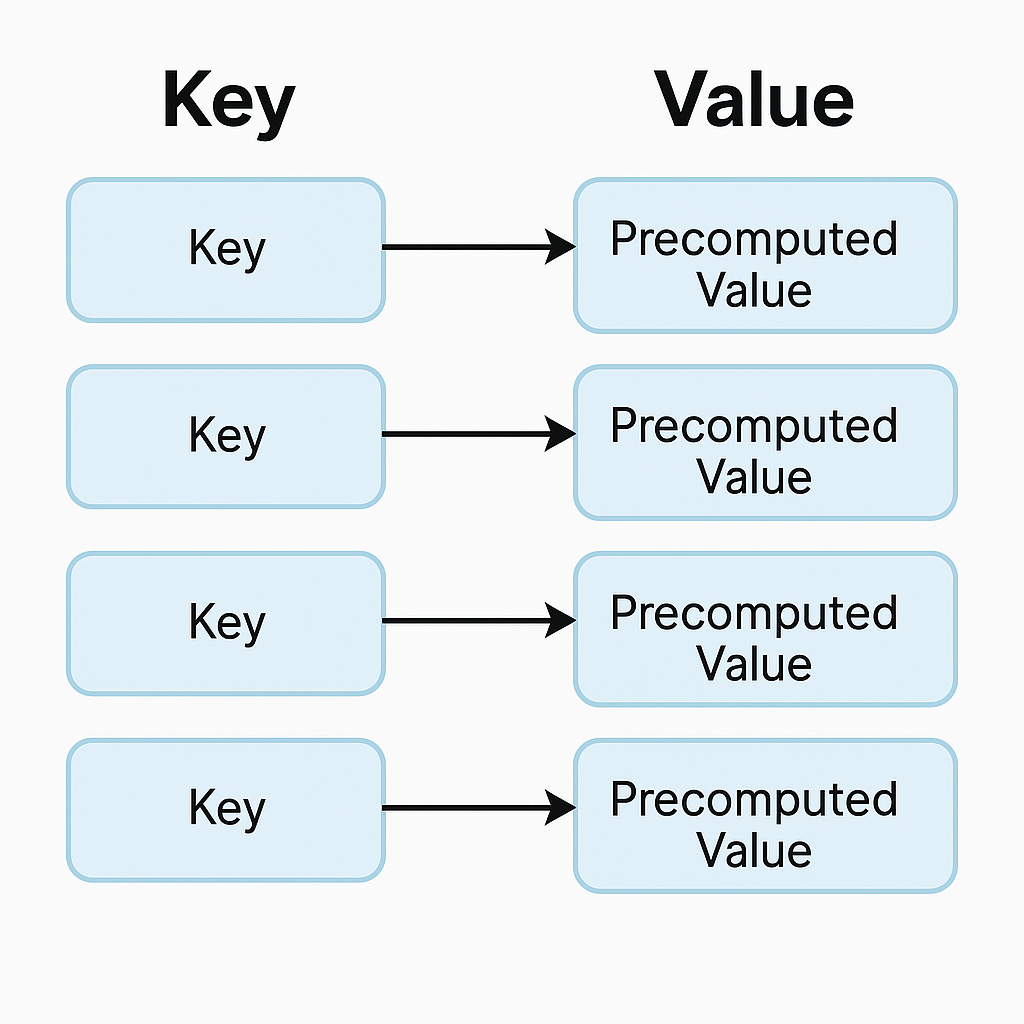

Dependency Injection typically involves the following components:

- Service (Dependency): The object that provides functionality (e.g., a database service, logging service).

- Client (Dependent Class): The object that depends on the service to function.

- Injector (Framework or Code): The mechanism responsible for providing the service to the client.

For example, in Java Spring:

- The database service is the dependency.

- The repository class is the client.

- The Spring container is the injector that wires them together.

Why is Dependency Injection Important?

DI plays a crucial role in writing clean and maintainable code because:

- It decouples the creation of objects from their usage.

- It makes code more adaptable to change.

- It enables easier testing by allowing dependencies to be replaced with mocks or stubs.

- It reduces the “hardcoding” of configurations and promotes flexibility.

Benefits of Dependency Injection

- Loose Coupling: Clients are independent of specific implementations.

- Improved Testability: You can easily inject mock dependencies for unit testing.

- Reusability: Components can be reused in different contexts.

- Flexibility: Swap implementations without modifying the client.

- Cleaner Code: Reduces boilerplate code and centralizes dependency management.

When and How Should We Use Dependency Injection?

- When to Use:

- In applications that require flexibility and maintainability.

- When components need to be tested in isolation.

- In large systems where dependency management becomes complex.

- How to Use:

- Use frameworks like Spring (Java), Guice (Java), Dagger (Android), or ASP.NET Core built-in DI.

- Apply DI principles when designing classes—focus on interfaces rather than concrete implementations.

- Configure injectors (containers) to manage dependencies automatically.

Real World Examples of Dependency Injection

Spring Framework (Java):

A service class can be injected into a controller without explicitly creating an instance.

@Service

public class UserService {

public String getUser() {

return "Emre";

}

}

@RestController

public class UserController {

private final UserService userService;

@Autowired

public UserController(UserService userService) {

this.userService = userService;

}

@GetMapping("/user")

public String getUser() {

return userService.getUser();

}

}

Conclusion

Dependency Injection is more than just a pattern—it’s a fundamental approach to building flexible, testable, and maintainable software. By externalizing the responsibility of managing dependencies, developers can focus on writing cleaner code that adapts easily to change. Whether you’re building a small application or a large enterprise system, DI can simplify your architecture and improve long-term productivity.

Recent Comments