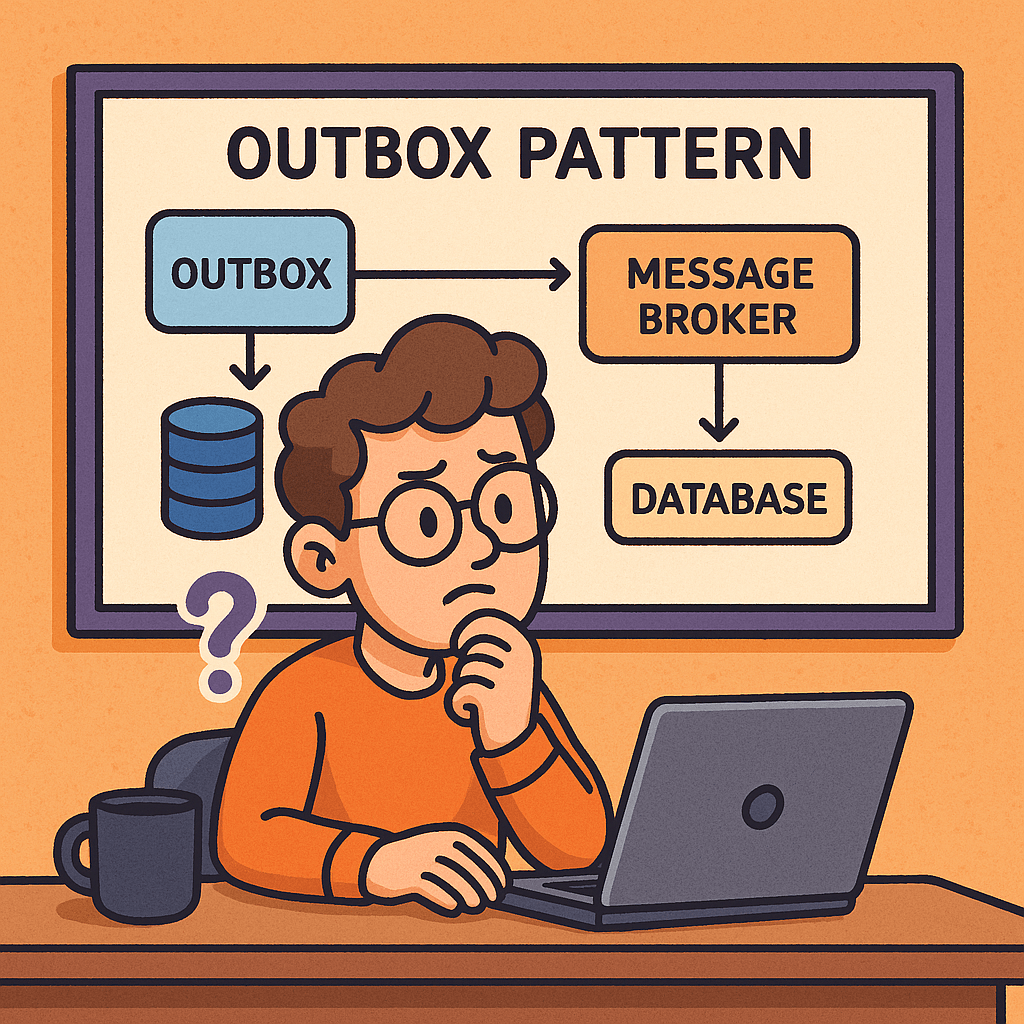

What is the Outbox Pattern?

The Outbox Pattern is a design pattern commonly used in distributed systems and microservices to ensure reliable message delivery. It addresses the problem of data consistency when a service needs to both update its database and send an event or message (for example, to a message broker like Kafka, RabbitMQ, or an event bus).

Instead of directly sending the event at the same time as writing to the database, the system first writes the event into an “outbox” table in the same database transaction as the business operation. A separate process then reads from the outbox and publishes the event to the message broker, ensuring that no events are lost even if failures occur.

How Does the Outbox Pattern Work?

- Business Transaction Execution

- When an application performs a business action (e.g., order creation), it updates the primary database.

- Along with this update, the application writes an event record to an Outbox table within the same transaction.

- Outbox Table

- This table stores pending events that need to be published.

- Because it’s part of the same transaction, the event and the business data are always consistent.

- Event Relay Process

- A separate background job or service scans the Outbox table.

- It reads the pending events and publishes them to the message broker (Kafka, RabbitMQ, AWS SNS/SQS, etc.).

- Marking Events as Sent

- Once the event is successfully delivered, the system marks the record as processed (or deletes it).

- This ensures events are not sent multiple times (unless idempotency is designed in).

Benefits and Advantages of the Outbox Pattern

1. Guaranteed Consistency

- Ensures the business operation and the event are always in sync.

- Avoids the “dual write” problem, where database and message broker updates can go out of sync.

2. Reliability

- No events are lost, even if the system crashes before publishing to the broker.

- Events stay in the Outbox until safely delivered.

3. Scalability

- Works well with microservices architectures where multiple services rely on events for communication.

- Prevents data discrepancies across distributed systems.

4. Resilience

- Recovers gracefully after failures.

- Background jobs can retry delivery without affecting the original business logic.

Disadvantages of the Outbox Pattern

- Increased Complexity

- Requires maintaining an additional outbox table and cleanup process.

- Adds overhead in terms of storage and monitoring.

- Event Delivery Delay

- Since events are delivered asynchronously via a polling job, there can be a slight delay between database update and event publication.

- Idempotency Handling

- Consumers must be designed to handle duplicate events (because retries may occur).

- Operational Overhead

- Requires monitoring outbox size, ensuring jobs run reliably, and managing cleanup policies.

Real World Examples

- E-commerce Order Management

When a customer places an order, the system stores the order in the database and writes an “OrderCreated” event in the Outbox. A background job later publishes this event to notify the Payment Service and Shipping Service. - Banking and Financial Systems

A transaction record is stored in the database along with an outbox entry. The event is then sent to downstream fraud detection and accounting systems, ensuring that no financial transaction event is lost. - Logistics and Delivery Platforms

When a package status changes, the update and the event notification (to notify the customer or update tracking systems) are stored together, ensuring both always align.

When and How Should We Use It?

When to Use It

- In microservices architectures where multiple services must stay in sync.

- When using event-driven systems with critical business data.

- In cases where data loss is unacceptable (e.g., payments, orders, transactions).

How to Use It

- Add an Outbox Table

Create an additional table in your database to store events. - Write Events with Business Transactions

Ensure your application writes to the Outbox within the same transaction as the primary data. - Relay Service or Job

Implement a background worker (cron job, Kafka Connect, Debezium CDC, etc.) that polls the Outbox and delivers events. - Cleanup Strategy

Define how to archive or delete processed events to prevent table bloat.

Integrating the Outbox Pattern into Your Current Software Development Process

- Step 1: Identify Event Sources

Find operations in your system where database updates must also trigger external events (e.g., order, payment, shipment). - Step 2: Implement Outbox Table

Add an Outbox table to the same database schema to capture events reliably. - Step 3: Modify Business Logic

Update services so that they not only store data but also write an event entry in the Outbox. - Step 4: Build Event Publisher

Create a background service that publishes events from the Outbox to your event bus or message queue. - Step 5: Monitor and Scale

Add monitoring for outbox size, processing delays, and failures. Scale your relay jobs as needed.

Conclusion

The Outbox Pattern is a powerful solution for ensuring reliable and consistent communication in distributed systems. It guarantees that critical business events are never lost and keeps systems in sync, even during failures. While it introduces some operational complexity, its reliability and consistency benefits make it a key architectural choice for event-driven and microservices-based systems.

Recent Comments