The rapid evolution of AI tools—especially large language models (LLMs)—has brought a new challenge: how do we give AI controlled, secure, real-time access to tools, data, and applications?

This is exactly where the Model Context Protocol (MCP) comes into play.

In this blog post, we’ll explore what MCP is, what an MCP Server is, its history, how it works, why it matters, and how you can integrate it into your existing software development process.

What Is Model Context Protocol?

Model Context Protocol (MCP) is an open standard designed to allow large language models to interact safely and meaningfully with external tools, data sources, and software systems.

Traditionally, LLMs worked with static prompts and limited context. MCP changes that by allowing models to:

- Request information

- Execute predefined operations

- Access external data

- Write files

- Retrieve structured context

- Extend their abilities through secure, modular “servers”

In short, MCP provides a unified interface between AI models and real software environments.

What Is a Model Context Protocol Server?

An MCP server is a standalone component that exposes capabilities, resources, and operations to an AI model through MCP.

Think of an MCP server as a plugin container, or a bridge between your application and the AI.

An MCP Server can provide:

- File system access

- Database queries

- API calls

- Internal business logic

- Real-time system data

- Custom actions (deploy, run tests, generate code, etc.)

MCP Servers work with any MCP-compatible LLM client (such as ChatGPT with MCP support), and they are configured with strict permissions for safety.

History of Model Context Protocol

Early Challenges with LLM Tooling

Before MCP, LLM tools were fragmented:

- Every vendor used different APIs

- Extensions were tightly coupled to the model platform

- There was no standard for secure tool execution

- Maintaining custom integrations was expensive

As developers started using LLMs for automation, code generation, and data workflows, the need for a secure, standardized protocol became clear.

Birth of MCP (2023–2024)

MCP originated from OpenAI’s efforts to unify:

- Function calling

- Extended tool access

- Notebook-like interaction

- File system operations

- Secure context and sandboxing

The idea was to create a vendor-neutral protocol, similar to how REST standardized web communication.

Open Adoption and Community Growth (2024–2025)

By 2025, MCP gained widespread support:

- OpenAI integrated MCP into ChatGPT clients

- Developers started creating custom MCP servers

- Tooling ecosystems expanded (e.g., filesystem servers, database servers, API servers)

- Companies adopted MCP to give AI controlled internal access

MCP became a foundational building block for AI-driven software engineering workflows.

How Does MCP Work?

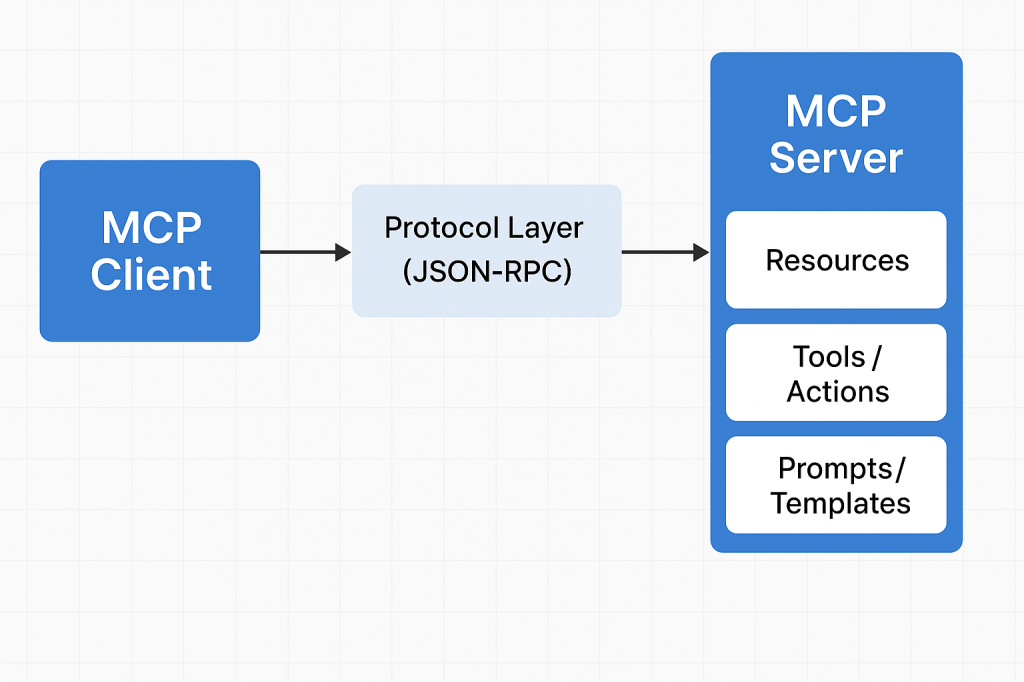

MCP works through a client–server architecture with clearly defined contracts.

1. The MCP Client

This is usually an AI model environment such as:

- ChatGPT

- VS Code AI extensions

- IDE plugins

- Custom LLM applications

The client knows how to communicate using MCP.

2. The MCP Server

Your MCP server exposes:

- Resources → things the AI can reference

- Tools / Actions → things the AI can do

- Prompts / Templates → predefined workflows

Each server has permissions and runs in isolation for safety.

3. The Protocol Layer

Communication uses JSON-RPC over a standard channel (typically stdio or WebSocket).

The client asks:

“What tools do you expose?”

The server responds with:

“Here are resources, actions, and context you can use.”

Then the AI can call these tools securely.

4. Execution

When the AI executes an action (e.g., database query), the server performs the task on behalf of the model and returns structured results.

Why Do We Need MCP?

– Standardization

No more custom plugin APIs for each model. MCP is universal.

– Security

Strict capability control → AI only accesses what you explicitly expose.

– Extensibility

You can build your own MCP servers to extend AI.

– Real-time Interaction

Models can work with live:

- data

- files

- APIs

- business systems

– Sandbox Isolation

Servers run independently, protecting your core environment.

– Developer Efficiency

You can quickly create new AI-powered automations.

Benefits of Using MCP Servers

- Reusable infrastructure — write once, use with any MCP-supported LLM.

- Modularity — split responsibilities into multiple servers.

- Portability — works across tools, IDEs, editor plugins, and AI platforms.

- Lower maintenance — maintain one integration instead of many.

- Improved automation — AI can interact with real systems (CI/CD, databases, cloud services).

- Better developer workflows — AI gains accurate, contextual knowledge of your project.

How to Integrate MCP Into Your Software Development Process

1. Identify AI-Ready Tasks

Good examples:

- Code refactoring

- Automated documentation

- Database querying

- CI/CD deployment helpers

- Environment setup scripts

- File generation

- API validation

2. Build a Custom MCP Server

Using frameworks like:

- Node.js MCP Server Kits

- Python MCP Server Kits

- Custom implementations with JSON-RPC

Define what tools you want the model to access.

3. Expose Resources Safely

Examples:

- Read-only project files

- Specific database tables

- Internal API endpoints

- Configuration values

Always choose minimum required permissions.

4. Connect Your MCP Server to the Client

In ChatGPT or your LLM client:

- Add local MCP servers

- Add network MCP servers

- Configure environment variables

- Set up permissions

5. Use AI in Your Development Workflow

AI can now:

- Generate code with correct system context

- Run transformations

- Trigger tasks

- Help debug with real system data

- Automate repetitive developer chores

6. Monitor and Validate

Use logging, audit trails, and usage controls to ensure safety.

Conclusion

Model Context Protocol (MCP) is becoming a cornerstone of modern AI-integrated software development. MCP Servers give LLMs controlled access to powerful tools, bridging the gap between natural language intelligence and real-world software systems.

By adopting MCP in your development process, you can unlock:

- Higher productivity

- Better automation

- Safer AI integrations

- Faster development cycles

Recent Comments